|

As the vernal equinox arrives and the changing of the clocks approaches, it is impossible not to take each seasonal event as a sign. The evidence of what is to come accumulates with every passing week.

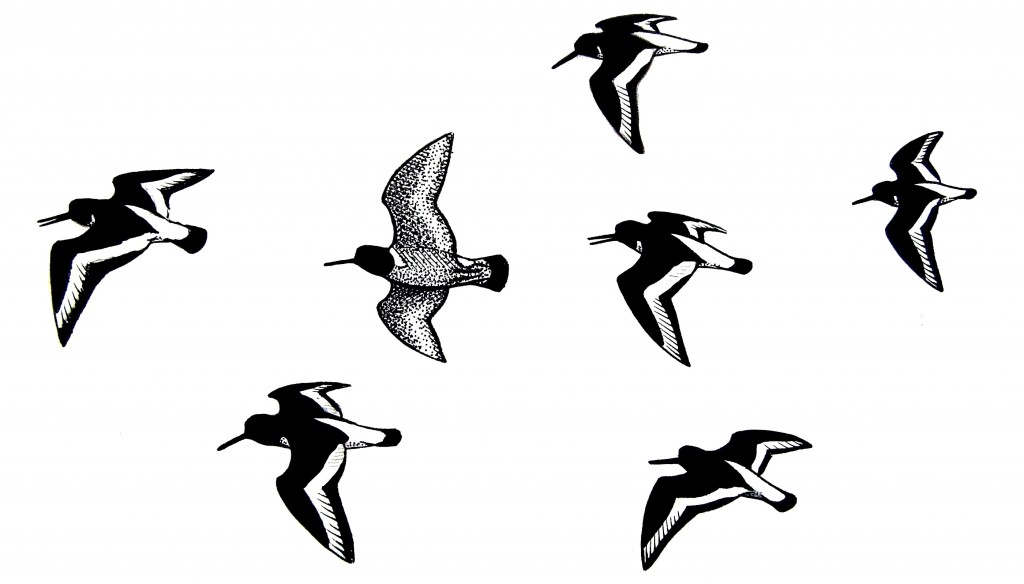

Officially, spring begins today. But our equilux – the day on which sunrise and sunset are closest to 12 hours apart – fell on the 17th, when the sun rose at twelve minutes past six in the morning and set just about the same time in the evening. Next weekend, the hours will push ahead and the night will be further delayed. These dates are useful. They are certain and predictable events, to be marked in the calendar ahead of time. They can be looked forward to patiently, in the knowledge that nothing is going to get in their way. But unless one never ventures outside, these events hardly count among the most significant signals of an unfolding spring. The lengthening of the day is a subtle process – part of an ongoing, gradual change. And though it may seem rapid at this time of year, as the darkness of winter lifts and the light stretches out into the evening, there are other signs of the season that are more dramatic and instantaneous, like a lightning spark of deja vu. There are, most particularly, the firsts of spring. In some places, the first cuckoo is such a sign. Though it is not heard, usually, until late April, that most unmistakable of calls is a confirmation that spring has fully sprung. In two short, unembellished notes, the first cuckoo tells the time of year. It reminds and reassures that summer is almost upon us. But cuckoos do not breed in Shetland, and they are only occasional visitors. To hear one would be a shock, for their song is not part of our spring. Instead, it is other sounds that usher in the season. The earliest of these, beginning at the end of January or early February, is the shrill pleepsing of oystercatchers – shalders, as they are known here – which call frantically in flight, as though always escaping catastrophe. Black and white with bright orange legs and beak, the birds seem almost to blink as they shudder overhead in flocks, like a semaphore warning of imminent, unseen danger. But it is not danger that the shalders herald; it is winter’s end. In the past week, I have heard my first skylark of the year – altogether a more joyful performance than that of the oystercatchers. Like cuckoos, larks are more often heard than seen, and on clear, still days, their song is carried so perfectly that it seems almost to become a part of the air itself. It shimmers like heat haze, as bright as the blue sky. It insists on an audience. The skylark, more than any other bird, holds within its extravagant melodies not just the promise of a summer to come, but the echoes of summers past. It brings both memory and premonition. That tiny creature, invisible against the day glare, swallowed up within the net of its own song, can be the biggest, most perfect piece of the day. At the moment, the garden is filling up. The first daffodils are about to open, and the flowering currants are looking their best. A dwarf rhododendron, spindly and wind-battered, has set for several weeks like a cloud of pink above its gnarled trunk – the trumpet flowers so delicate and flawless that they seem not to belong to the same plant as those few salt-burned leaves that it still can muster. After the horrors of winter, each bud and each flower brings a kind of relief. They offer a confirmation that, even here, where winter lingers so long, the inevitable will, eventually, come. Among the trees, blackbirds are bustling again. These ones are probably just passing through, on their way to more northerly places. So too the lone song thrush that scuttled about the garden one morning last week. The rush of migrants has not yet truly begun. For now there is only a gradual increase in voices. There are common gulls and curlews; there are calls I recognise but for which I have no name. From the bushes, today, there was the whispered whistle of a goldcrest. From now the signs will keep coming. The first wheatears will arrive soon; the first skuas and arctic terns; the first swallows and meadow pipits. And soon, too, the fields will fill with lambs, each one bursting with the sudden revelation of spring. I can’t remember exactly how old I was when I was given my first camera, but I can remember the camera. It was a Kodak Instamatic: a little box of plastic and metal that took square photographs, four by four inches. Probably I still have it somewhere, tucked away among other relics that will never again find a purpose, but from which it is difficult to part.

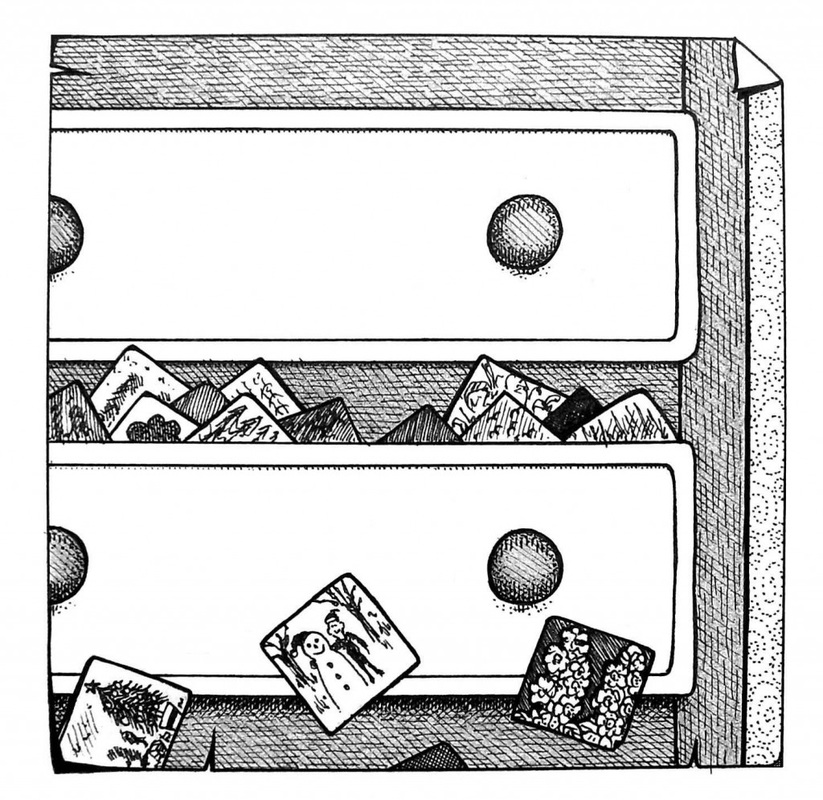

I seem to think that I carried that camera everywhere, and probably made a nuisance of myself with it, too. Certainly, when I was a little older and had graduated to a model capable of capturing rectangular images, I took a lot of photographs. I was, for a time, obsessed. In the days before digital, a click of the shutter was not an inconsequential thing. Each such click would eventually come back to you, tucked inside stiff paper folders, as a record of your memories and your mistakes. For always there were mistakes: strange, indistinct blurs; ghostly faces lost in ultra-soft focus. These photographs, both good and bad, accumulated over several years inside a drawer in my bedroom. Rarely looked at, but regularly added to, the pictures piled up higher and higher until that drawer would neither open nor close without considerable difficulty. And then, in a moment of youthful impetuosity, I threw them away. Aged 16, perhaps, I piled scores of those envelopes, with hundreds of photographs and negatives, into a black plastic bag and disposed of them, saving just a few dozen pictures. It was a stupid thing to do, and I regretted my decision at exactly the moment I realised it was too late to get them back. Today, I can’t remember any of those images, but I wish that I could see each one of them again, blurs and all. Those few pictures that were saved are now gathered in a single album: a highly edited gallop through my mid-childhood years, right up to the point – not long after I threw away those pictures – when I gave up photography as a hobby. Among the twenty or so remaining images that were taken with the Instamatic are two or three family portraits. In one, my parents and my brother are seated in front of a Christmas tree, probably on the day I was given the camera. Empty wrapping paper lies strewn on the sofa beside them. In a second, my brother stands with his arm around a snowman’s shoulders, the pair of them smiling broadly despite the cold. Another of those early pictures – this one crudely cut into an even smaller square – shows a dense cluster of flowers, somewhat misfocused but still impressive. It is a burst of shocking pink blossoms, like an explosion of confetti. The plant was one that I had grown, when I was aged just eight or nine. I had put the seeds into the ground and then forgotten about them. No foresight, no care. Until this marvellous thing had appeared. I don’t know why I recall this, but I do: they were Brompton stocks. And there were two clumps of them, one pink and one white. They were the first flowers for which I had ever been responsible, and for a long time they were the last. I took the picture because I was proud of them. The plants were big and the blooms extravagant. And despite the absence of care or attention in my cultivation technique, I was fairly proud of myself, too. I can still remember an elderly woman stopping to admire the display as she passed our driveway. And I can remember the disbelief in her voice when I told her that it was me who was the gardener. For years now, that early burst of horticultural enthusiasm has lain dormant. I have had no further interest in flowers. When I have thought of them at all I have thought of them as a waste of energy and space, and I have limited my involvement with gardening to the purely utilitarian: vegetables for food, trees for shelter. The rest: superfluous. Recently, though, as the first blooms of spring began to emerge, something changed. I was reminded again of those glorious Brompton stocks, and of that little photograph. I am relieved now that I kept it, and that it did not end up, like so many others, in the bottom of a black bag. But I think that had it been lost, or even had it never been taken, I would still have remembered. And I think, too, that I would still have changed my mind. For where else do we find pleasure but in the superfluous? And where else can pleasure be so easily cultivated but in the garden? |

The Things Around MeThe Things Around Me is the story of a Shetland garden, written by Malachy Tallack and illustrated by Will Miles.

Archives

October 2016

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed