|

At eight o'clock, the garden was ripe with shadows, each one sharpening against the dull edge of the morning. Gradually, a grim pink was unveiled through cloud cracks in the east, then lost again. And by the time the sun rose, just after ten past nine, grey daylight hung low over the valley, as though weighed down by the effort of its own becoming. There was no bright sunrise, no glorious, golden dawn, only a slow and reluctant undarkening.

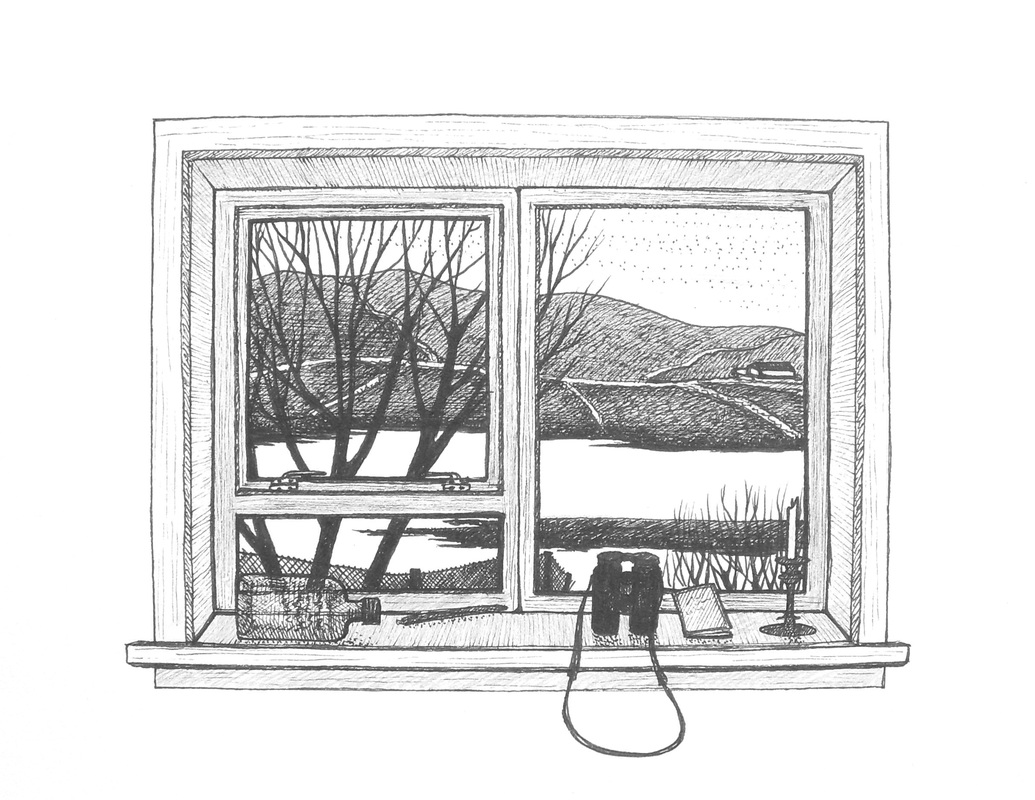

This was the shortest day: midwinter. Most often it falls earlier, on the 21st, but it seemed that even the solstice was sluggish this year. Today, the sun held above the horizon for just over five and a half hours. Tomorrow, the nights will begin to shorten and the days to lengthen out. Spring, I suppose, is on the horizon. I did not rise easily. During the night I was woken by the wind, then held awake by the rushing of my own thoughts. It took me a long time to sleep again. When I opened my eyes just before eight, both had quietened, though not entirely calmed. The first sound I heard was the chattering of crows from just outside. These grey mornings make it hard to be cheerful. Particularly when they give way to grey afternoons and black, starless nights. They make it hard not to long for winter to pass, and for warmth to creep in again, spreading generous green light around the garden. I longed for that today as I watched dawn roll so hurriedly into darkness. Of course, there are few things more stupid than longing life away. Each day that falls behind is one fewer left ahead, and even as I gaze impatiently into the garden, I regret my willingness to wish a winter gone. I regret how one moment after another can pass with such terrifying haste and yet still seem to be moving too slow. But it seems I cannot help it, and that troubles me. It keeps me awake at night. Bound up tightly with all this wasteful impatience is a kind of physical restlessness that is as familiar as it is unwelcome. At this time of year, it pulls at my sleeve like an impatient child, urging me to go and to keep going. There are, in Shetland, those who acknowledge that pull and follow it. A few spend their summers here in the islands and then fly south – usually to New Zealand – to enjoy another summer. Like migrating birds, these people stay always a step ahead of winter. Perfectly natural, some might say. Perfectly normal. We are, after all, a restless species: nomads, wanderers, pilgrims. One thinks here of Bruce Chatwin, and his claim that 'Evolution intended us to be travellers'. Human beings are hard wired to keep moving, he insisted, and their relatively recent propensity to stop and settle down has led to all manner of social and psychological problems. 'I like to think that our brains have an information system giving us our orders for the road' he wrote, 'and that here lies the mainsprings of our restlessness'. The only antidote, according to Chatwin at least, is to heed its call and go. But mostly I do not go. Mostly I resist. And in part I resist because I disagree. Restlessness is not a craving that can be satisfied simply by giving in. It is not a thing that can be physically escaped or left behind. Like an itch, the scratching of it does not always soothe; it may exacerbate. But I resist, too, for another reason. Wherever I have travelled in the world, and for whatever reason I have gone, my restlessness has morphed almost invariably into homesickness. My thoughts, which here will wander towards paradises not yet found, soon make their way back to that paradise I have left behind. And the longer I stay away, the more insistent these thoughts become. In the late 17th century, when homesickness was first described by the physician Jonnaes Hofer, it was given the medical name, nostalgia, derived from Greek and meaning, roughly, the suffering caused by a longing to return. Hallucinations, nausea, loss of appetite and indifference to the world were among the many symptoms. Those who suffered most were invariably soldiers, most often from Switzerland or from Scotland. City dwellers rarely succumbed; those from farms and rural areas were worst affected. Over the years, there were numerous suggested remedies for this strange and debilitating illness: leeches, opium, purging of the stomach, busying oneself with 'manly' activities and, during the American Civil War, public ridicule. But ultimately most doctors agreed that there was only one guaranteed cure, and that was to go home. And so here I am, afflicted by restlessness when at home and by homesickness when away. One might be forgiven for pronouncing mine a hopeless case. And one might well be right. But while these two urges have seemed to rage and argue within me always, I am no longer convinced that they are in fact so very different. Rather, I wonder if they might not be, at root, two strains of the same malady: one, a longing for an imagined future; the other, for an imagined past. Both restlessness and homesickness are symptomatic of a disengagement from the present moment and the present place – an exile that manifests itself as an impulse to flee, either in one direction or the other. Evaluating our own emotions, we routinely misdiagnose the causes of that impulse, but it seems to me that somewhere at the heart of it all must be the desire to end our exile – to become fully present – and to be, in every sense, at home. So why then are my feet and fingers twitching? Why do I hear this siren song, persuading me to go? In what way am I disconnected from the now and the here in which I find myself, on this black evening, in this chair beside the window? The answer may be simple. It may be only that I am on the wrong side of the glass. In these short, dark days, I am not often outside. My experience of the things around me is mostly indirect and non-participatory. I see the garden for a few hours and then it is gone. And if I did not work from home, I would barely see it at all. For most people in Shetland, at this time of year, it is dark when they leave home in the morning and dark when they get back at night. For five or six days in a week, the world outside is known only by memory. I suspect that were I to be out there every day, either working in the garden or even just crawling about in the dirt, I would be a more satisfied person. I would be cold and damp much of the time, but this in itself would not equal unhappiness. Indeed it would surely engender a deeper sense of gratitude for those comforts that I find inside the house. I would be healthier, being well exercised, and I would certainly sleep better at night. I have a feeling too that my restlessness would weaken, and that perhaps I would be more fully here. Such a life has its appeal, undoubtedly, but without a farm or a croft it is hardly a practical option. While I might enjoy hauling on my wellies every morning and splashing around in the mud, a full time devotion to such activities might require certain personal and financial sacrifices. And because of that – because it is optional – a bit of bad weather is enough to keep me inside for days at a time. There is surely a discipline, then, to engaging more fully with place. I am thinking not just of a determination to go outside, whatever the weather, but of a kind of attentiveness – a conscious effort to notice and to be aware – that might bring one's surroundings more clearly into focus. In suggesting this, I am skirting deliberately around the word mindfulness, and pushing towards something less centred on the self. That something could best be called placefulness: a way of imagining and understanding one's relationship with place and one's participation within it; a way of acknowledging those connections that bind us to the present place and time; a way of living with both past and future, without longing for either. The problem with the shortest day is that it is gone too quickly. In these mid-winter weeks, light arrives then disappears, and the opportunities to enjoy it pass swiftly by. And when the night does come and darkness surrounds the house, I find myself standing sometimes beside the window, looking out to where the garden ought to be. With the lights switched on and the world wrapped in black, the cold glass becomes a mirror. All I can see there is myself. The windows at the back of the house – in the bedroom, living room and dining room – face east, across the loch. In the morning, if the sun shines, it shines into these rooms.

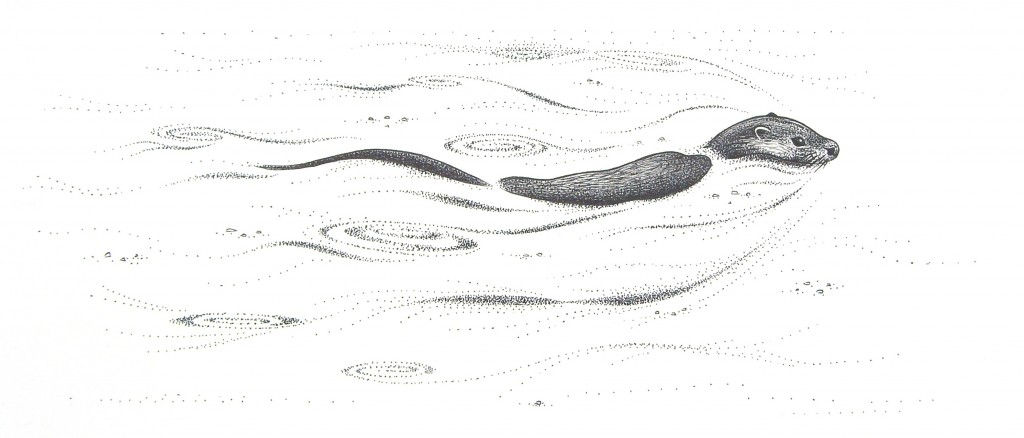

Being very easily distracted, I often find myself staring out of one or other of these windows before I start work in the morning and again at various points during the day. When light allows, I stare out in the evening too. I suppose that I must look as though consumed by thought at these times – troubled, perhaps, or at least engaged in sober contemplation – for I am often asked “What’s wrong?” or “What are you worrying about?” My answer – “Nothing” – rarely seems to suffice. But the truth is, for the most part, that I am not thinking. Or at least I am not thinking consciously or purposefully. I am not seeking solutions to problems. I am not, more’s the pity, crafting perfect lines of prose. I am merely watching, and seeing how the pieces come together. This morning, looking northeast to where the loch slips under the bridge and into the sea, a mirror calm wedge of water was broken by swirls and splashes. My view was obscured from the bedroom window by tall bushes in the garden, so I moved to where the binoculars were sat on the sill in the dining room and looked again. The swirls were still there, and in that uncertain movement the disturbance became a black shape, which became, in turn, an otter. I saw the head first, then as it rolled to dive the arc of its back lifted, followed by the tail, like a thick eel protruding momentarily from the water. It was hardly gone ten seconds before it returned, swirling again, swimming in the direction of the house. Slipping just beneath the surface, it careered sideways, dragging a shallow bow wave behind it. For a moment I couldn’t see the animal, only the wake it left as it swam. And then it was up again, spilling broad circles of light over the loch. While otters in Shetland do most of their hunting in the sea, they must swim in freshwater regularly to wash the salt from their fur and keep it in good condition. Since there are certainly otters living somewhere close the village, it is surprising how few times we have seen them over these past six months. In the summer, one individual bumbled down the path, past the front door and then disappeared into the garden. But for the most part they have been remarkably elusive. Visitors to Shetland are generally keen to see two things in particular: puffins and otters. The former are easy, at the right time of year. They are bold and camera-friendly, posing unhurriedly at cliff edges, with their brightly coloured beaks resplendent in the summer light. Otters, on the other hand, are masters of invisibility. Even the best local guides would not be so foolish as to guarantee a sighting. And yet sometimes, like this morning, they are apparently determined to be seen. They make no attempt to be discreet, even in a place like this, with houses and human activity all around. They just carry on, almost oblivious. By this time, the otter was almost out of sight, having come so close to the house that it was hidden by the bushes and short wall at the end of the lawn. I grabbed my boots and hauled them on, slipping quietly out of the door and making my way down to ‘the forest’, where I thought I’d have the best chance of getting nearer. Stepping slowly and (I thought) quietly down from the gate I saw no sign of it, so kept going. Then, as I reached halfway towards the water, it was there: the dark shape on the surface, now very close to the shore. I could see the strange, serpentine movement of it, as though the animal had no backbone to contend with. It splashed and curled and dived and rose, hunting perhaps, though in a perfectly leisurely way. The morning was colder than I’d expected, and I was uncomfortable there without my coat. It made me impatient, and I took my next step without looking where I was going. A twig broke loudly in the still air, and when I looked up again I could see the place where the otter had been. Several moments passed, but I saw nothing more – only the memory of it spreading out in bright loops across the loch. If there is one thing upon which it is almost possible to depend in Shetland’s unpredictable and eclectic climate, it is the wind. As an exposed and relatively low-lying archipelago in the North Atlantic, we get our fair share and more of strong winds, gales and storms. The upper echelons of the Beaufort Scale are familiar – sometimes wearyingly familiar – territory.

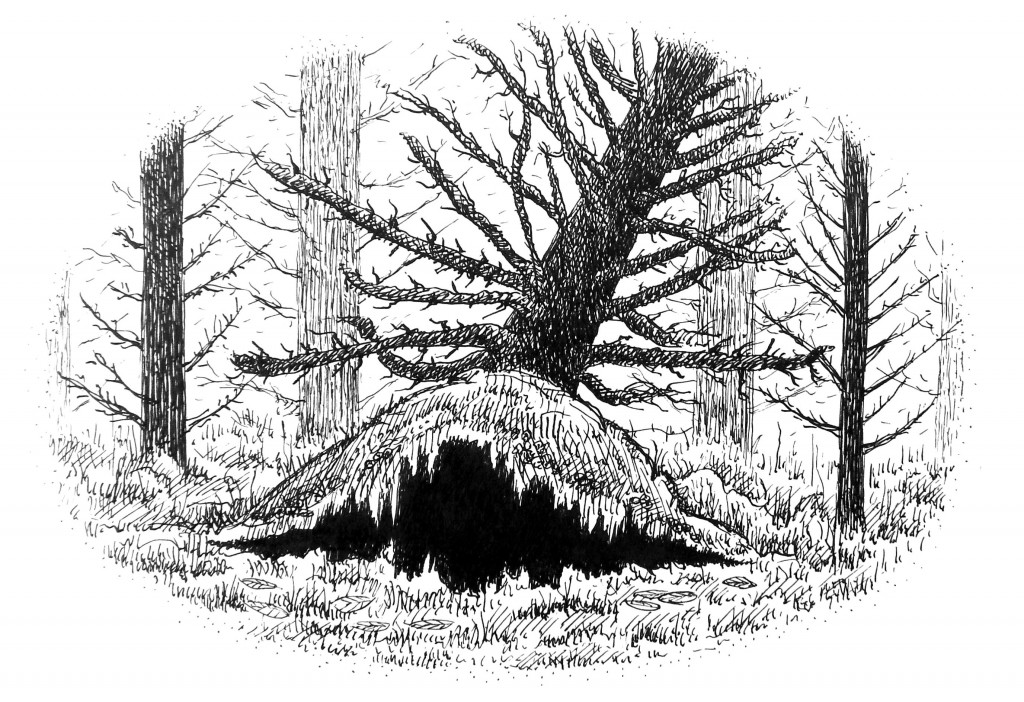

Over the past couple of weeks, we have been treated to several, sometimes prolonged, incursions into that territory. Gale has followed gale, with little respite between. Twelve days ago a gust of 90 miles per hour was recorded; and last night was even worse, with gusts reaching up to almost 100 miles per hour. This is not exceptionally strong for a Shetland winter, but it has been particularly unremitting. As in all places where extremes of weather are to be expected, life adjusts. Buildings are constructed with winter in mind, and when forecasts are bad, anything that might move is either tidied up or tied down: plant pots, wheelbarrows, sheds, caravans. It is remarkable what a bit of wind can do. Inside, we separate ourselves from it, sheltering in our bubbles of stillness – behind curtains, beside fires. Like passengers in a speeding car, we are disconnected from the violent pace of what surrounds us. But when the wind really blows, as it did last night, it becomes impossible to hide from it. The air whistles under doors; it batters and rattles windows; it howls and growls and hisses and screams. A strange, inexplicable fear can rise out of this din: the fear, perhaps, of being consumed by something wild and monstrous. “I always feel the wind as a bad-tempered thing” wrote John Stewart Collis, “and my mind contracts in resisting it, and I can enjoy no pleasant, expansive thoughts when ruffled by its peaceless, ceaseless wave”. This morning did not exactly bring calm – a force eight gale blew for much of the day, with gusts of 60 miles an hour or so – but the worst of the storm had passed. There was that shimmering sense of relief that comes when a threat is lifted – when the grizzly bear steps away from the cabin door and the sound of its bellow abates. At once, other details emerge. You become aware, firstly, of yourself: the stiff heartbeat and the first conscious breath. Then the world, as it was, returns. I took a walk around the garden this afternoon, looking for damage and for an excuse to be outside. On a whim, I hopped up on to the wall below the ‘upper’ trees, and pushed my way in among them. At once I felt more sheltered and more vulnerable than I had outside. Here the wind was changed – not subdued, exactly, but constrained, as though held on a fraying leash. The sound was amplified, too, roaring up among the evergreens, which swayed precariously and unpredictably beneath the weight of the air. Here and there were broken branches, hanging loose or lying where they’d fallen among the rotting leaves. One tree had tipped a little, exposing a wedge of severed roots and soil. Then, further up, a pine was leaning over at 45 degrees, resting hard against the trunk of another. At its base was a semicircle of earth about three metres across, with a dark hollow lying beneath. There was something poignant about this sight, and I walked slowly around it, reminded again of somewhere far away and long ago. I was six years old, almost seven, when the ‘Great Storm’ of October 1987 hit, blowing over an estimated 15 million trees in Britain. I can just recall walks near our home in the south of England in the months that followed, among forests changed forever by the strength of that wind. And it is those hollows that come back to me most clearly – deep holes in the ground where roots once had been, with headstones of earth now towering above. A biting shower of snow bristled around me as I stood there beside the tree, watching it, still rocking gently from the force of the wind, like the quieting beat of a heart. 13th December That last storm was followed by three days of cold and relative calm, the loch shifting between light ripples and mirror stillness, edged by a fragile skin of ice. The valley becomes smaller at such times. Sound is unhindered. The bark of a dog from across the water is loud and disconcerting. The yell of a crow seems to come from everywhere at once. Stillness like this does not feel like a zero point or a state of equilibrium, but, rather, like an absence of wind. Calm, in its way, is just as shocking as a gale. If there is balance, it lies somewhere in between. |

The Things Around MeThe Things Around Me is the story of a Shetland garden, written by Malachy Tallack and illustrated by Will Miles.

Archives

October 2016

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed