|

Autumn in Shetland can be the shortest and most ill-defined of seasons. It comes and is gone in the rushing of air. Gales drag summer southwards, leaving behind a space that autumn must fill. But gales do not stay silent for long, and winter begins quickly to press itself upon us.

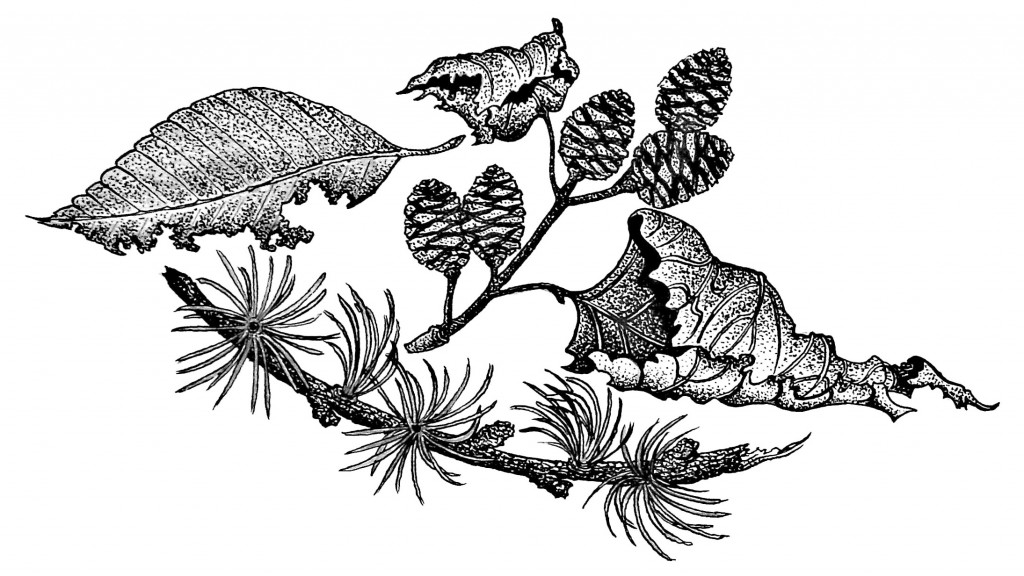

Here the season is marked most clearly by the passage of birds and, for some, by work. Lambs are sold and slaughtered; vegetables are taken from the ground. The traditional signs of autumn elsewhere – the yellows and reds and the falling leaves – are not entirely familiar in Shetland, where trees are uncommon and mostly diminutive. But here in this house, we are lucky. The southern border of the garden is marked by trees – a line of 100 metres or so, by ten wide, sloping down from the road to the bank of the Vidlin Loch. That slope is divided both physically, by a wall and a fence, and botanically, into three roughly equal parts. At the top, closest to the road, are densely planted conifers – mostly shore pines and Sitka Spruce, if my identification skills are to be trusted. These are big trees by Shetland standards; the largest are fifteen, maybe twenty metres tall. Here, trunks and branches are tangled, and the light struggles to break through. Walking in among them, pushing limbs and needles out of the way, it is possible to feel a great distance from home. Below them, in the middle part of the garden, closest to the house, the cover is broken and the trees are mostly shorter. There is a diverse, somewhat eccentric mix here, both evergreens and deciduous, as well as a few feeble currant and raspberry bushes, clumps of fuchsia and a very un-northern sprouting of pampas grass. The lower section of the garden – ‘the forest’ – holds a mixture of well established trees, most likely planted when the house was built back in the late forties. It is enclosed on all sides by a fence, yet it feels, undeniably, the most ‘natural’ part of the garden, if such a label can be comfortably applied, which of course it cannot. There are firs and spruce here, two kinds of willows, hawthorns, sycamore and others. I recognise some but several remain a mystery. I am frustrated by my ignorance. On an afternoon between gales I took an identification book – newly purchased for the purpose – and wandered slowly beneath branches, pausing beside each anonymous tree. Blackbirds harangued me from above, and two robins, recently arrived, watched my progress with apparent concern. A tiny Shetland wren (Troglodytes troglodytes zetlandicus) crept like a mouse among fallen leaves. Even with this book though I struggled. Most branches are now bare, and to uninitiated eyes like mine the differences are hard to distinguish. Those leaves that remain are largely in poor condition, fragile and discoloured. I have picked the wrong time of year to educate myself. And what is worse, I had been forewarned that Shetland’s climate can produce trees quite distinct from textbook examples of the species. The odds were not on my side, and I barely knew where to start. After twenty minutes or so, cold and frustration pushed me back inside, and I returned to the dining table with an armful of leaves and twigs and cones, determined to make at least semi-informed guesses at all of them. With the book in front of me, I sat down and picked at random. A leaf, about ten or twelve centimetres long, roughly oval in shape, but pointed at the end and more rounded towards the base. The edges were toothed and 14 or 15 veins spread out on either side of the midrib. Despite being one of the last on the tree, the leaf had retained most of its colour. Only a light singeing of the apex and teeth gave away the season. Immediately I was stuck. The closest image I could find was of a wild cherry, though that seemed improbably exotic for a Shetland garden. But perhaps not. Unsure, I moved on.There were some I was confident about. The larch was unmistakable – splayed tufts of yellowing needles all along the rough-skinned branch – and the three-part leaves of a laburnum were equally unambiguous. There were two alders, I think, of two different varieties; the cones, though more or less equal in size, were quite distinct in appearance. But again, I had little confidence in this conclusion. Of the others, one more was familiar: the scaly green fronds of a cypress tree. The look and, more particularly, the smell of it dragged me unexpectedly back to a place quite distant from here. I couldn’t picture it at first, but then I remembered: the garden of my paternal grandparents – both long dead now – in the Sussex town where I spent the first years of my life. Not all of it comes back to me, but I remember the square lawn that my grandfather cut slowly and meticulously with his push mower. And beyond it I can see the trees: a tall oak in the centre and a broad holly bush to one side. Behind them were others – a world to explore – and somewhere in that garden, I am certain, were cypress trees. As a child I would run and hide among them, the soft leaves brushing against my face, the scent of them in my nostrils. It seems strange that a smell would stay with me for so long, yet somehow I am relieved to have found it again. When I returned to the table the following morning the leaves had dried and curled in upon themselves. The larch needles too had begun to loosen, and as I ran my finger over them, a shower of yellow exclamations fell, leaving the twig bare and almost ugly. The table was strewn with the victims of my curiosity, brittle and withered after just a few hours inside. All except the cypress fronds, which looked and smelled exactly as they did the day before, and exactly as they did more than 20 years ago. As the light drew back over the hills to the west and a soupy gloom slunk in around the garden, I crouched down at the tiny plot of vegetables sheltering beside the south wall of the greenhouse. At five square metres or so it is not exactly providing for all our needs, but this is almost as much as we have managed in this first year of growing.

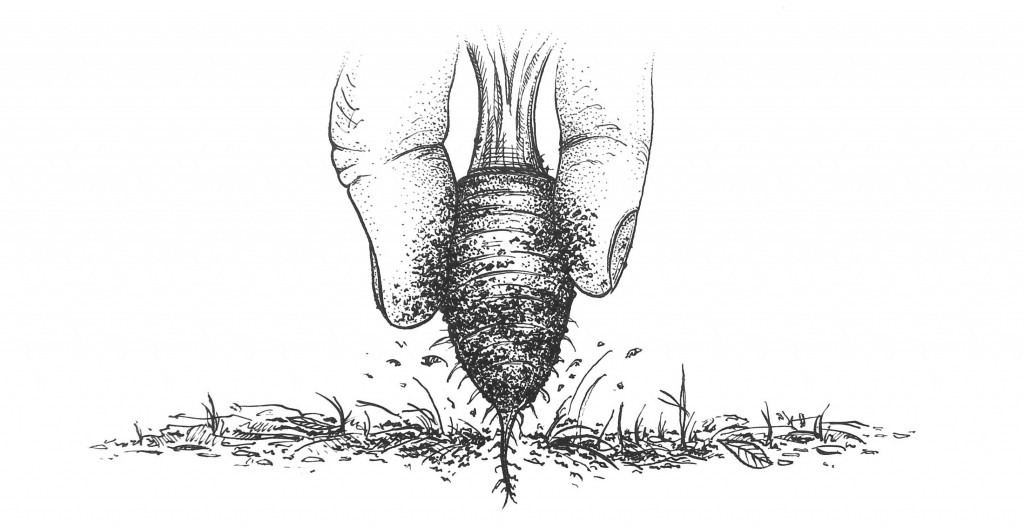

The soil is damp but not too cold, and I press my fingers in around the stubby-bodied carrots and pull. They are a disappointing treasure, emerging finger-length at best, with most even shorter than that – an inch or two of root to show for a whole summer’s patience. Autumn King this variety is called, but these specimens look more runtish than regal. The fault is not in the seed though; the fault is in the soil.There have been successes this year – a great bounty of fat courgettes, some salad leaves, lettuce and a few spring onions – but our first attempt at coaxing vegetables from this ground has been largely disappointing. We started late, if truth be told. When the house became ours, at the end of March, our first priority was inside. Day after day was spent hauling out carpets, tearing down plasterboard, insulating, sanding, painting, varnishing. Stripped wallpaper piled up around us like fronds of damp, claggy seaweed, and it seemed we might never escape from the mess or make this house into a home. Beyond a few brief excursions, the garden was almost ignored. On one dry day I tried to turn over a patch of the scrubby back park for planting, but layers of thick roots and stony soil resisted both spade and rotavator. All big plans were laid to rest and alternatives were temporarily postponed. The backup scheme was simple, born of limited time, energy and easily clearable space. We planted potatoes, onions and a few brassica seedlings in the vaguely brown square I had scraped out of the back park; courgettes, cucumbers, peppers, salad and tomatoes went in the greenhouse; and we squeezed whatever we could fit into the narrow bed just outside, from which I’d hauled several overgrown clumps of Lady’s Mantle and other unidentified plants. There were numerous disappointments through the summer. Out the back, the onions and brassicas failed to grow at all, though the tatties – Cara, Kestrel and Shetland Blacks – did well. In the greenhouse, tomatoes refused to ripen and peppers failed to flourish. In the little bed, almost everything is stunted – the beetroot, neeps and cabbage, the leeks and parsnips, the tiny carrots. The soil is just not good enough for vegetables, it seems. And making it good will take work. It will take time. Compost and manure are needed; seasons of gradual improvement are required. The feel of those little roots between my fingers reminded me that, if we wish to continue, it will not be a case of just planting and hoping for the best. We will need to make more effort. We will need to think about the soil. Not so long ago, owning a house seemed like a great responsibility and a greater commitment. But now I’m not so sure. Ownership itself commits us to nothing, and leaves us responsible for not much more than payment. The desire to grow bigger carrots, however: that is a commitment. The soil demands fidelity – a virtue that has no place in the housing market – and it asks for care. If we can leave things at least as good as when we found them then perhaps that is good enough. Perhaps that is the best that we can do. I gathered a few things together – the mud-coated carrots, a fist-sized neep and a courgette from the greenhouse. The blackcap was calling again from the back park, with a staccato signal that bristled the air. And then a response. Another bird. Then another. And another. Five blackcaps were scattered around the garden, announcing themselves in the gathering night. I could see none of them, but I listened on until the birds were silent again, then carried the vegetables into the house, where the smell of cooking had already filled the warm, bright kitchen. Ten days have passed and the garden feels a different place altogether. The warmth has gone, flushed out with the first of the season’s gales, and what is left is brittle and transient. Colours are changing – rich greens fading to olives and browns – and there is a yellowing of the air now, which pales quickly to grey as evening arrives. When the sun comes it rarely stays for long.

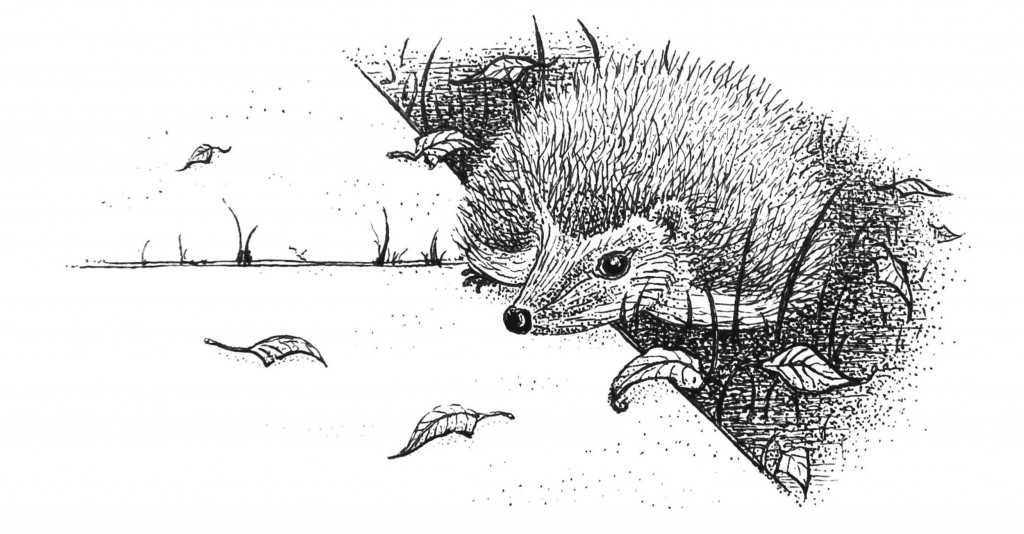

Trees and bushes are growing gaunt, their skeletal frames emerging from behind the summer attire. Leaves scuttle like crabs about the garden’s edge, and in the long untended grass. The last autumn crocuses have abandoned their show and drooped, leaving only two lonely poppies and the gangly monkshood still in bloom – brash, blue and deadly. Overhead, geese move together in broad wing-strides, their ragged arrow formation pointing the way towards winter. The sound of them falls like hail over the valley. This is an unsettling time. Everything is changing; each day, each hour is different. Knowing this place now, as it turns through this restless season, seems impossible. Like a lover whose temperament – whose very face – alters from one moment to the next, the land has become elusive, mysterious, enigmatic. It has left me lost. Beyond the window, a blackcap flits from elsewhere to here. He visits the little goat willow often, and I sit, distracted, watching him fluster among the branches, picking intently at invisible things. Now and then he stops, looks out over the garden and offers an alarm call: chack-chack-chack-chack. He waits and listens, but nothing responds. This bird should be on his way to somewhere else by now, and I expect each day for him to be gone. He arrived a couple of weeks ago, together with a female (whose cap is not black but chestnut brown). The female though has disappeared, and I wonder if he is still waiting for her to return. I wonder about this particularly because, while I hope that she has flown south, I fear that our cat may have been responsible for the disappearance. In my guilt I have written tragedy into the tale, and a grief that most likely cannot exist. As I sit watching the bird, a movement beyond catches my eye. At the edge of the overgrown lawn a little hedgehog is nosing through the leaves and the dirt. His tiny feet take him in and out among the plants, as he weaves his way through the flowerbed. There is an urgency to his movements, and to his daylight appearance, which suggest that all is not well. Hibernation cannot be far away, and maybe this one understands he is not yet big enough to survive.I step out from the living room and up the path, to where the hedgehog has paused. It does not try to escape as I approach; nor does it attempt to roll up into a ball. The little creature simply lumbers from one edge of the path to the other, uncertain of what to do next. I wonder if perhaps he is no less lost than me out here. He knows this garden from one angle only, and has just a few months of life behind him. Maybe next year, with another summer and a long winter under his prickly belt he’ll be a wiser thing, but for now we might not be so different. I let the hedgehog shuffle back into the flowerbed while I shuffle back to a warm house and a cup of tea. I sit down again in my chair by the window, and think of the great, impossible allure of hibernation. It is right, I suppose, to be lost at this time – to feel pulled by an ebbing tide. The things around me are unsettled and uncertain, and to be immune from that uncertainty would be to miss a point. I could close these windows and doors, draw the curtains and turn up the heating. I could climb into bed and stay there till springtime. I could shut my eyes and imagine myself flying south. But then where would I be? There is a conversation going on, and I am part of it. Or at least, I want to be a part. There are words whose sound is strange and whose meaning is uncertain; there are signals and signs that I cannot yet follow. There is a language, not foreign but unfamiliar. I am trying to listen. And I am trying to learn. |

The Things Around MeThe Things Around Me is the story of a Shetland garden, written by Malachy Tallack and illustrated by Will Miles.

Archives

October 2016

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed