|

On dry days I have been outside as much as time allows, finding jobs to do in the greenhouse or among the borders, or just walking through the garden and watching as things progress. Beneath the trees, scores of green shoots are growing taller. Daffodils and bluebells are among them, though only the snowdrops and purple crocuses, which crouch timidly under bare bushes, have opened so far.

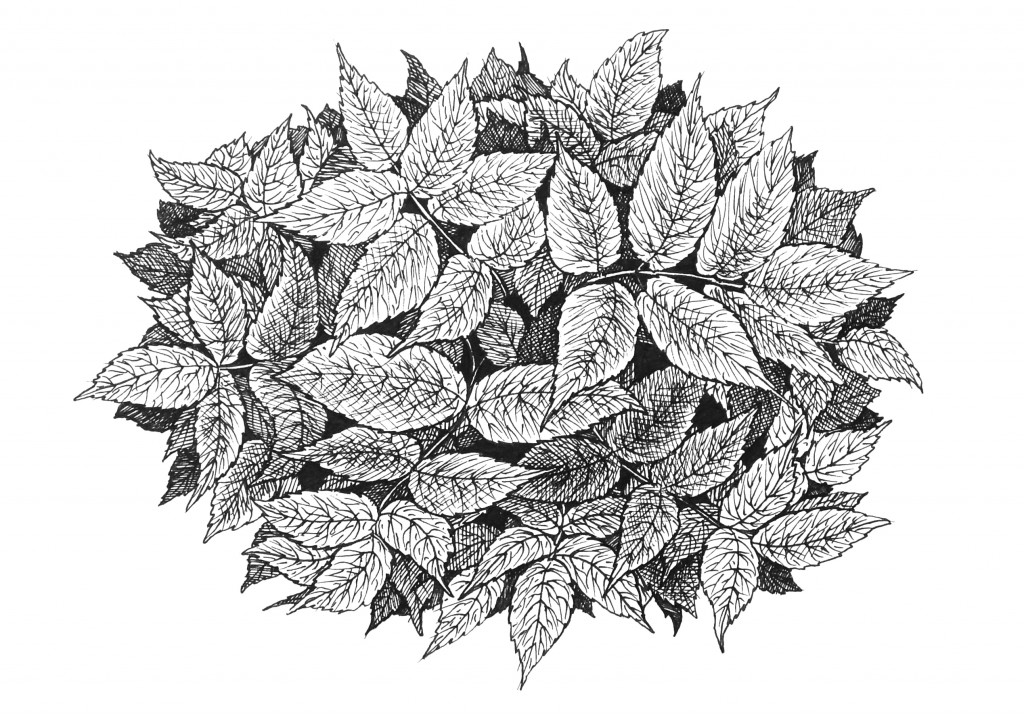

There is a kind of relief to be found on these wanders. At times when I feel burdened by the thought of tasks as-yet-undone, it makes me glad to see what flourishes without any intervention. These bulbs would grow whether I was here or not; they are reliable, predictable, determined. My pleasure at these sights though has been tempered by the appearance of another early riser: an unwelcome guest in the garden. On the edges of the upper and lower patches of trees, in the back park and throughout the semicircular flower bed in front of the house, clusters of bright green leaves are emerging and unfurling, pushing their way up towards the light. Being an entirely inexperienced gardener, I had no clue about the identity of this plant when we first moved here, less than a year ago. And even when I was informed of its name – ground elder – it meant nothing. Now, however, the sight of these new leaves makes me shudder. Before long they will have grown into a rampant, sprawling mass, like an infection in the earth. Ground elder is among the most feared of weeds, and for good reason. It is extremely invasive, and can quickly dominate a garden, swamping and crowding out other plants. It is also extraordinarily difficult to remove once established. And established it certainly is. Part of the problem with ground elder is that it spreads below the soil as well as above it. Long threads of root, called rhizomes, extend outward from each plant, sometimes in several directions. And as these rhizomes burrow away from the parent, they send up new shoots, gathering more energy and taking up more space. The result is a tangle of leaves above ground, and a tangle of roots below it. It is difficult not to ascribe evil intentions to such a species. There is something monstrous and nightmarish about this plant, after all. I imagine it like an enormous web, spread out beneath the surface of the garden, and at its centre, somewhere, must be a dark heart. Find that, and the beast may be slain. Sadly, the truth is worse: there is no heart to find. To kill ground elder it must be removed completely, piece by piece, or else starved of light for long enough to stop it growing. The former method is more practical for most people, but more risky. For like a severed tentacle that can regenerate an octopus, the tiniest piece of root left in the ground will grow again. Digging it out must be done with care – slowly and meticulously. The only other alternative is chemical weedkiller, to which, in agonising defeat, many a committed organic gardener must have been driven. It is standard practice these days to extend a certain sympathy towards weeds. These plants that cause so much trouble and frustration can become metaphorically entangled with the idea of ‘wildness’. In this conception, weeds are the forces of the wild, fighting against the civilising army of people, clawing back the land that we try to domesticate. It is them against us. For the most part, this is nonsense. And in the case of ground elder, it is complete nonsense. Weeds are exploiters of the human; they thrive because we thrive. More urban fox than timber wolf, their preferred natural habitat is not a wilderness, it is a cultivated garden with a lazy gardener. The history of ground elder is inseparable from the history of people. For this is not a native Shetland species, reclaiming its territory. Nor is it even a native British species. Ground elder was taken north from continental Europe as a food source by the Romans, who found the British Isles rather lacking in edible greenery. Later, in the Middle Ages, it was moved around by monks, who considered it a cure for the gout with which they were plagued. Today, it is mainly gardeners who carry it from place to place (as well as the wind, of course). A tiny sliver of rhizome hidden among the roots of an ornamental plant, transferred from one garden to another, is all it takes to cause a whole lot of trouble. That, most likely, is how our own colony arrived. Walking the edge of the curved flower bed out front, which is riddled with the stuff, I leant down and plucked a few of the plants. In Scandinavia, it is still often eaten, either raw in salad or cooked as an alternative to spinach, and I put these tiny leaves in my mouth and chewed. They were tangy – an odd, distinctive flavour that I certainly wouldn’t call pleasant. Not good enough to forgive the weed; and certainly not good enough to allow it to remain. As morning folded into afternoon, I set out for the shed beneath the garage with an ambitious aim in mind. Behind the door, with its peeling red paint, lay an ungainly heap of scrap wood and broken furniture. All winter I had been delaying the job of turning this pile of rubbish into neater and more useful pieces of firewood and kindling. But now was the time. Very soon, a solid fuel stove will be installed in our kitchen, and the idea of feeding it for free, at least for a while, was enough to tempt me out with the saw.

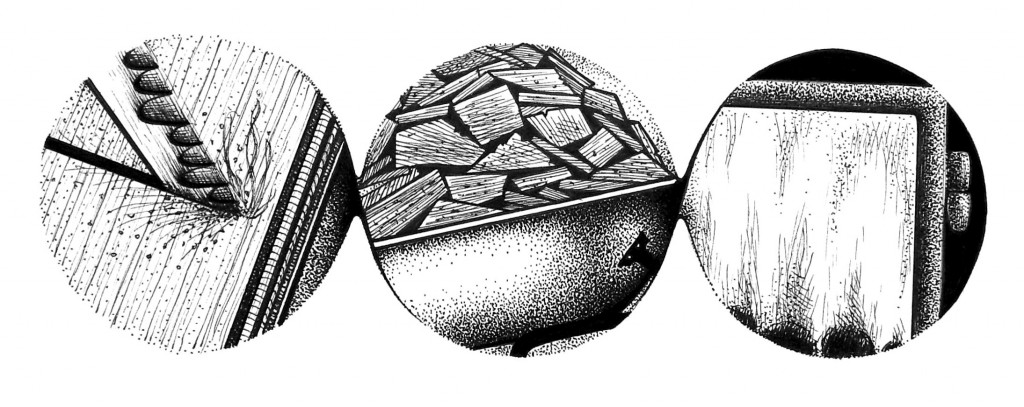

Inside the shed, the wood was strewn carelessly about, in all shapes and sizes. There was an old chest of drawers – warped by damp, and broken on top – and two squat cupboards, no longer usable. Several retired fence posts were stacked at the back, along with two or three thick logs which must have been cut from a fallen tree in the garden. Most of the wood though had built up during our work on the house over the past year: countless lengths of skirting board and v-lining, assorted scraps and offcuts, all thrown haphazardly into the shed, awaiting another use. Delving among it, I found many of the pieces familiar. As I picked them up and turned them over, I remembered the day on which they were discarded or the room from which they came. I recalled their various histories, and how they intertwined with my own. All of them now will end up in the same place, warming the house they helped to build. I gathered an armful of long sections – mostly skirting board from the dining room – and lay them outside on the ground; the smaller pieces I threw into a wheelbarrow by the doorway. When the barrow was full, I pushed it along to the work bench I’d set on the path and put it down on the far side, in easy reach. The afternoon was still. Out on the water, only a light ripple twisted the reflection of the houses across the loch and the half-clear sky. It seemed rude to be interrupting the day’s calm with the growl of an electric saw, but I didn’t have much choice. To attempt to cut all of this by hand would be a full time occupation. I would certainly warm myself with the effort, but I might never have the time to enjoy the heat of it burning. I had no option but to be noisy. Once plugged in and switched on, the blade cut easily, with a steady downward pressure. An incision, a wound, an amputation. It was rhythmic, almost hypnotic. The uniqueness of each piece of wood and its individual resistance to the blade became an irrelevance; every cut was exactly like the last. There was at first something disappointing about this. It was a strangely detached activity. My actions were machine-like and repetitive. Where sawing by hand demands energy and effort, all that this task required of me was time and electricity, and enough concentration to keep my fingers clear of the blade. There was no sweat on my brow and no ache in my muscles. The only slight discomfort was a niggling boredom at the rather mindless work. Yet the growing pile of wood was certainly satisfying. A few scattered chunks grew quickly into a mound of fire sized pieces. And when the first barrow load was finished, I filled another. And another. Wisps of sawdust rose like yellow smoke as the logs continued to clatter to the ground. I kept on like this for two hours, then three, without a pause. And while the work itself could hardly be called enjoyable, the result and the purpose were enough to keep me going. They were enough, even, to bring enjoyment. In another setting, such a job might be unbearably dull and robotic. But given reason for our efforts, the will becomes more robust and the work becomes easier. We need a point to our labour, it seems. In the end it was only hunger that brought me, almost reluctantly, back to the house, leaving behind two neat stacks of wood in the shed, all ready for the fire. Homecoming is the meeting between place and memory of place; it is the point at which past and present conjoin. And though the memory may be only weeks, days, or even hours old, there is always a distance to be crossed in the first moments of return. There is always a space between what is remembered and what is newly experienced.

When I stepped off the bus, just outside the front gate, it was lunchtime and the day was surprisingly mild. I was tired after travelling from Aberdeen on the boat overnight, and I was still a little shaky. It seemed the motion of the sea – which early in the morning had been throwing my belongings impetuously around the cabin – had been imprinted into my own muscles. It was a deep, shivering reflex that wore off only after several hours on dry, unmoving land. I walked slowly down towards the house, carrying my suitcase high so as not to drag it through the chicken shit that speckled the path. I’ve been away from home only three weeks. That’s not enough to leave me surprised by what has altered in my absence, but enough to be aware that it has altered. I looked around, trying to note the changes individually, but it was not easy to do. Defining the space between what is seen and what is remembered is hardest in those things most familiar to us. Like staring in the mirror after days without seeing your own face: what was seems to dissolve instantly into what is. The garden contained within it an accumulation of movement and growth which, together, amounted to a kind of swelling. The shadow of vulnerability that had clung to the place through the winter had lessened – released its grip a notch, or maybe two. Certain greens now seemed richer and less hesitant. Certain bushes now seemed less deceased. Right down low, the first bulbs have become flowers. Tiny snowdrops hang their heads forlornly here and there among the borders, like monks or mourners at a funeral. Alone in their display, the snowdrops are reluctant pioneers. They gaze always at the ground, as though ruing the genetic clock that brings them out of the soil so early in the year. On a day such a this, when a rumour of warmth softens the air, it is tempting to see these little flowers as brave heralds of the season to come, quietly sharing their song of spring with the garden. But the message is misleading. Unless this year is unlike all others I have known in Shetland, there is plenty of winter yet to come. The snowdrops are liars, but still they are easily forgiven. Their song is dishonest, but it is sung sweetly. Out on the side lawn, close to the trees, were two rabbits. It is unusual to see them here, so near to the house. When we first moved they were treating the garden as their own. At least one burrow, and possibly several more, lay in the back park. And every day we would watch them munching happily on the grass and among the beds. But their boldness could not last, for the cat very quickly made it known that such behaviour was unacceptable. From now on, while they were welcome to hang around, the consequences of doing so were not going to be ideal for the rabbits. One or two began to appear, headless, on our doorstep, and very soon the garden was a bunny free zone. As winter drags on though, they must be straying further. The pickings will be getting slim in the safest places, and so they become a little braver, a little more desperate. Either that or the cat has got lazy since I went away. Stepping into the porch, I turned and closed the door behind me, then put my bag down and went to sit in the living room. I was not thinking of anything in particular, just waiting, as though to catch up with myself. I felt deflated, exhausted, and inexplicably nervous. I lay back on the sofa and closed my eyes, readying myself to get home. |

The Things Around MeThe Things Around Me is the story of a Shetland garden, written by Malachy Tallack and illustrated by Will Miles.

Archives

October 2016

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed