|

In the spring of 2011, I moved to a house on the northeast coast of the Shetland mainland. What attracted me to the place was not just the house itself but the garden, which was large and, unusually for Shetland, partly populated by trees.

The short essays here were an attempt to get to know this place, and the birds, animals and plants that lived there. Many of the ideas explored in these pieces would later be expanded in Sixty Degrees North. As the vernal equinox arrives and the changing of the clocks approaches, it is impossible not to take each seasonal event as a sign. The evidence of what is to come accumulates with every passing week.

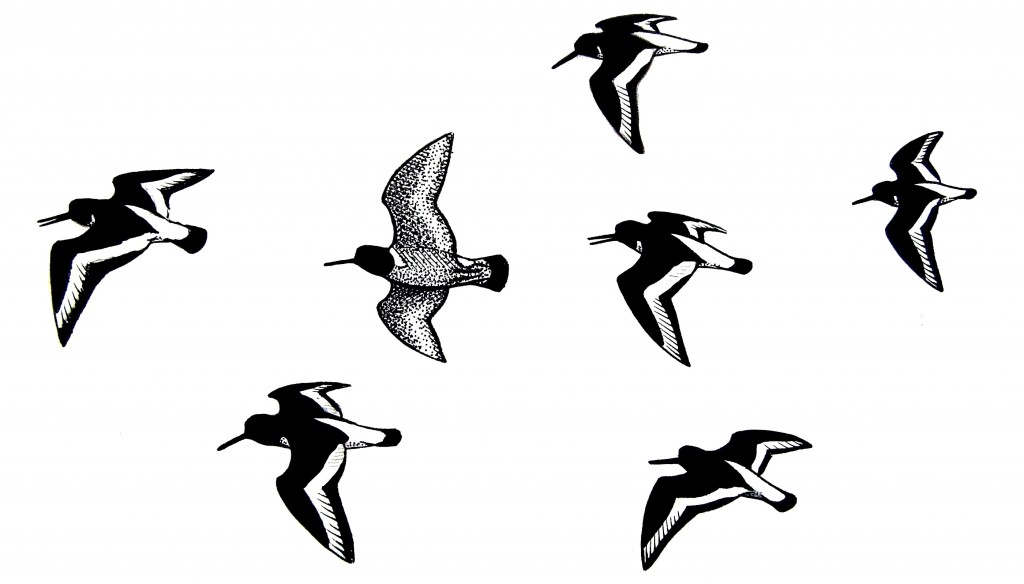

Officially, spring begins today. But our equilux – the day on which sunrise and sunset are closest to 12 hours apart – fell on the 17th, when the sun rose at twelve minutes past six in the morning and set just about the same time in the evening. Next weekend, the hours will push ahead and the night will be further delayed. These dates are useful. They are certain and predictable events, to be marked in the calendar ahead of time. They can be looked forward to patiently, in the knowledge that nothing is going to get in their way. But unless one never ventures outside, these events hardly count among the most significant signals of an unfolding spring. The lengthening of the day is a subtle process – part of an ongoing, gradual change. And though it may seem rapid at this time of year, as the darkness of winter lifts and the light stretches out into the evening, there are other signs of the season that are more dramatic and instantaneous, like a lightning spark of deja vu. There are, most particularly, the firsts of spring. In some places, the first cuckoo is such a sign. Though it is not heard, usually, until late April, that most unmistakable of calls is a confirmation that spring has fully sprung. In two short, unembellished notes, the first cuckoo tells the time of year. It reminds and reassures that summer is almost upon us. But cuckoos do not breed in Shetland, and they are only occasional visitors. To hear one would be a shock, for their song is not part of our spring. Instead, it is other sounds that usher in the season. The earliest of these, beginning at the end of January or early February, is the shrill pleepsing of oystercatchers – shalders, as they are known here – which call frantically in flight, as though always escaping catastrophe. Black and white with bright orange legs and beak, the birds seem almost to blink as they shudder overhead in flocks, like a semaphore warning of imminent, unseen danger. But it is not danger that the shalders herald; it is winter’s end. In the past week, I have heard my first skylark of the year – altogether a more joyful performance than that of the oystercatchers. Like cuckoos, larks are more often heard than seen, and on clear, still days, their song is carried so perfectly that it seems almost to become a part of the air itself. It shimmers like heat haze, as bright as the blue sky. It insists on an audience. The skylark, more than any other bird, holds within its extravagant melodies not just the promise of a summer to come, but the echoes of summers past. It brings both memory and premonition. That tiny creature, invisible against the day glare, swallowed up within the net of its own song, can be the biggest, most perfect piece of the day. At the moment, the garden is filling up. The first daffodils are about to open, and the flowering currants are looking their best. A dwarf rhododendron, spindly and wind-battered, has set for several weeks like a cloud of pink above its gnarled trunk – the trumpet flowers so delicate and flawless that they seem not to belong to the same plant as those few salt-burned leaves that it still can muster. After the horrors of winter, each bud and each flower brings a kind of relief. They offer a confirmation that, even here, where winter lingers so long, the inevitable will, eventually, come. Among the trees, blackbirds are bustling again. These ones are probably just passing through, on their way to more northerly places. So too the lone song thrush that scuttled about the garden one morning last week. The rush of migrants has not yet truly begun. For now there is only a gradual increase in voices. There are common gulls and curlews; there are calls I recognise but for which I have no name. From the bushes, today, there was the whispered whistle of a goldcrest. From now the signs will keep coming. The first wheatears will arrive soon; the first skuas and arctic terns; the first swallows and meadow pipits. And soon, too, the fields will fill with lambs, each one bursting with the sudden revelation of spring. I can’t remember exactly how old I was when I was given my first camera, but I can remember the camera. It was a Kodak Instamatic: a little box of plastic and metal that took square photographs, four by four inches. Probably I still have it somewhere, tucked away among other relics that will never again find a purpose, but from which it is difficult to part.

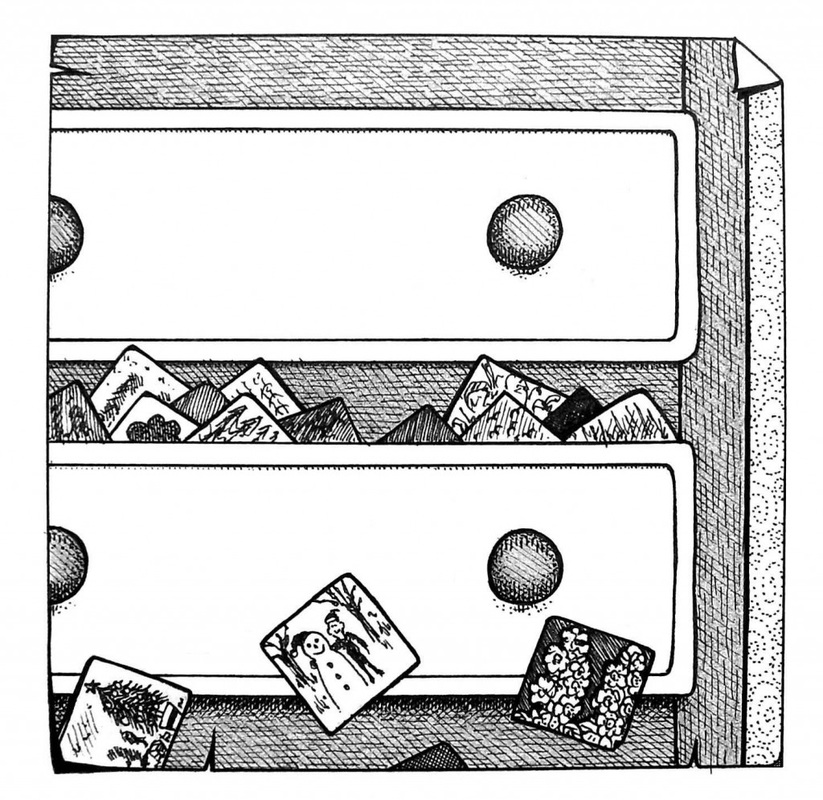

I seem to think that I carried that camera everywhere, and probably made a nuisance of myself with it, too. Certainly, when I was a little older and had graduated to a model capable of capturing rectangular images, I took a lot of photographs. I was, for a time, obsessed. In the days before digital, a click of the shutter was not an inconsequential thing. Each such click would eventually come back to you, tucked inside stiff paper folders, as a record of your memories and your mistakes. For always there were mistakes: strange, indistinct blurs; ghostly faces lost in ultra-soft focus. These photographs, both good and bad, accumulated over several years inside a drawer in my bedroom. Rarely looked at, but regularly added to, the pictures piled up higher and higher until that drawer would neither open nor close without considerable difficulty. And then, in a moment of youthful impetuosity, I threw them away. Aged 16, perhaps, I piled scores of those envelopes, with hundreds of photographs and negatives, into a black plastic bag and disposed of them, saving just a few dozen pictures. It was a stupid thing to do, and I regretted my decision at exactly the moment I realised it was too late to get them back. Today, I can’t remember any of those images, but I wish that I could see each one of them again, blurs and all. Those few pictures that were saved are now gathered in a single album: a highly edited gallop through my mid-childhood years, right up to the point – not long after I threw away those pictures – when I gave up photography as a hobby. Among the twenty or so remaining images that were taken with the Instamatic are two or three family portraits. In one, my parents and my brother are seated in front of a Christmas tree, probably on the day I was given the camera. Empty wrapping paper lies strewn on the sofa beside them. In a second, my brother stands with his arm around a snowman’s shoulders, the pair of them smiling broadly despite the cold. Another of those early pictures – this one crudely cut into an even smaller square – shows a dense cluster of flowers, somewhat misfocused but still impressive. It is a burst of shocking pink blossoms, like an explosion of confetti. The plant was one that I had grown, when I was aged just eight or nine. I had put the seeds into the ground and then forgotten about them. No foresight, no care. Until this marvellous thing had appeared. I don’t know why I recall this, but I do: they were Brompton stocks. And there were two clumps of them, one pink and one white. They were the first flowers for which I had ever been responsible, and for a long time they were the last. I took the picture because I was proud of them. The plants were big and the blooms extravagant. And despite the absence of care or attention in my cultivation technique, I was fairly proud of myself, too. I can still remember an elderly woman stopping to admire the display as she passed our driveway. And I can remember the disbelief in her voice when I told her that it was me who was the gardener. For years now, that early burst of horticultural enthusiasm has lain dormant. I have had no further interest in flowers. When I have thought of them at all I have thought of them as a waste of energy and space, and I have limited my involvement with gardening to the purely utilitarian: vegetables for food, trees for shelter. The rest: superfluous. Recently, though, as the first blooms of spring began to emerge, something changed. I was reminded again of those glorious Brompton stocks, and of that little photograph. I am relieved now that I kept it, and that it did not end up, like so many others, in the bottom of a black bag. But I think that had it been lost, or even had it never been taken, I would still have remembered. And I think, too, that I would still have changed my mind. For where else do we find pleasure but in the superfluous? And where else can pleasure be so easily cultivated but in the garden? On dry days I have been outside as much as time allows, finding jobs to do in the greenhouse or among the borders, or just walking through the garden and watching as things progress. Beneath the trees, scores of green shoots are growing taller. Daffodils and bluebells are among them, though only the snowdrops and purple crocuses, which crouch timidly under bare bushes, have opened so far.

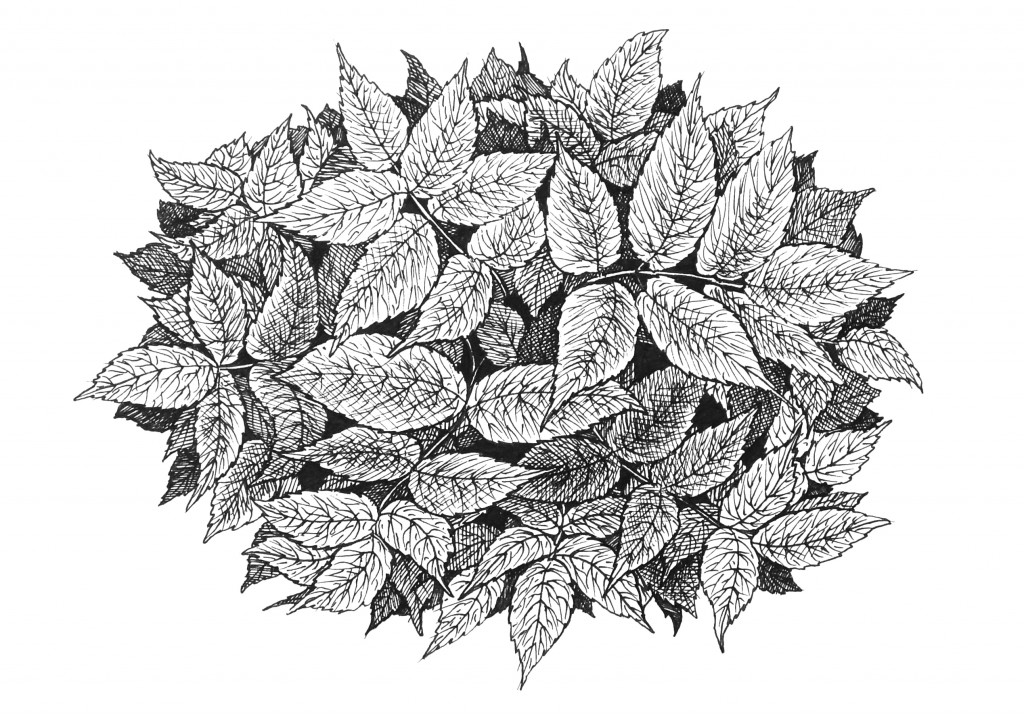

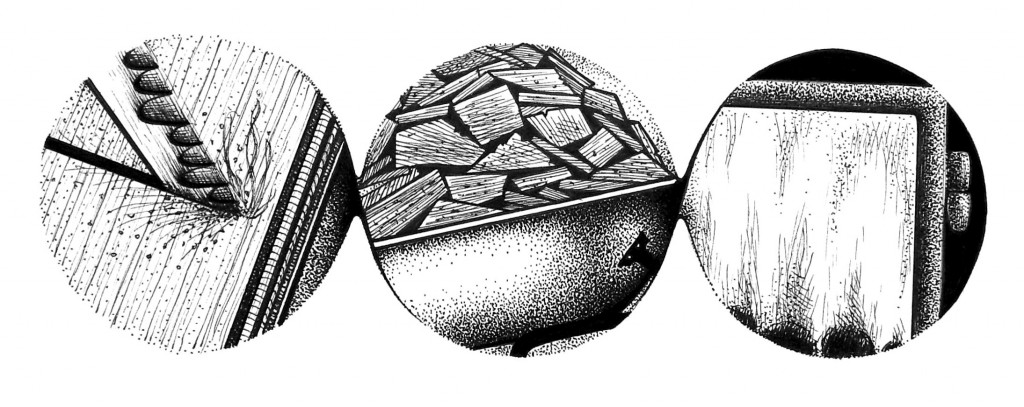

There is a kind of relief to be found on these wanders. At times when I feel burdened by the thought of tasks as-yet-undone, it makes me glad to see what flourishes without any intervention. These bulbs would grow whether I was here or not; they are reliable, predictable, determined. My pleasure at these sights though has been tempered by the appearance of another early riser: an unwelcome guest in the garden. On the edges of the upper and lower patches of trees, in the back park and throughout the semicircular flower bed in front of the house, clusters of bright green leaves are emerging and unfurling, pushing their way up towards the light. Being an entirely inexperienced gardener, I had no clue about the identity of this plant when we first moved here, less than a year ago. And even when I was informed of its name – ground elder – it meant nothing. Now, however, the sight of these new leaves makes me shudder. Before long they will have grown into a rampant, sprawling mass, like an infection in the earth. Ground elder is among the most feared of weeds, and for good reason. It is extremely invasive, and can quickly dominate a garden, swamping and crowding out other plants. It is also extraordinarily difficult to remove once established. And established it certainly is. Part of the problem with ground elder is that it spreads below the soil as well as above it. Long threads of root, called rhizomes, extend outward from each plant, sometimes in several directions. And as these rhizomes burrow away from the parent, they send up new shoots, gathering more energy and taking up more space. The result is a tangle of leaves above ground, and a tangle of roots below it. It is difficult not to ascribe evil intentions to such a species. There is something monstrous and nightmarish about this plant, after all. I imagine it like an enormous web, spread out beneath the surface of the garden, and at its centre, somewhere, must be a dark heart. Find that, and the beast may be slain. Sadly, the truth is worse: there is no heart to find. To kill ground elder it must be removed completely, piece by piece, or else starved of light for long enough to stop it growing. The former method is more practical for most people, but more risky. For like a severed tentacle that can regenerate an octopus, the tiniest piece of root left in the ground will grow again. Digging it out must be done with care – slowly and meticulously. The only other alternative is chemical weedkiller, to which, in agonising defeat, many a committed organic gardener must have been driven. It is standard practice these days to extend a certain sympathy towards weeds. These plants that cause so much trouble and frustration can become metaphorically entangled with the idea of ‘wildness’. In this conception, weeds are the forces of the wild, fighting against the civilising army of people, clawing back the land that we try to domesticate. It is them against us. For the most part, this is nonsense. And in the case of ground elder, it is complete nonsense. Weeds are exploiters of the human; they thrive because we thrive. More urban fox than timber wolf, their preferred natural habitat is not a wilderness, it is a cultivated garden with a lazy gardener. The history of ground elder is inseparable from the history of people. For this is not a native Shetland species, reclaiming its territory. Nor is it even a native British species. Ground elder was taken north from continental Europe as a food source by the Romans, who found the British Isles rather lacking in edible greenery. Later, in the Middle Ages, it was moved around by monks, who considered it a cure for the gout with which they were plagued. Today, it is mainly gardeners who carry it from place to place (as well as the wind, of course). A tiny sliver of rhizome hidden among the roots of an ornamental plant, transferred from one garden to another, is all it takes to cause a whole lot of trouble. That, most likely, is how our own colony arrived. Walking the edge of the curved flower bed out front, which is riddled with the stuff, I leant down and plucked a few of the plants. In Scandinavia, it is still often eaten, either raw in salad or cooked as an alternative to spinach, and I put these tiny leaves in my mouth and chewed. They were tangy – an odd, distinctive flavour that I certainly wouldn’t call pleasant. Not good enough to forgive the weed; and certainly not good enough to allow it to remain. As morning folded into afternoon, I set out for the shed beneath the garage with an ambitious aim in mind. Behind the door, with its peeling red paint, lay an ungainly heap of scrap wood and broken furniture. All winter I had been delaying the job of turning this pile of rubbish into neater and more useful pieces of firewood and kindling. But now was the time. Very soon, a solid fuel stove will be installed in our kitchen, and the idea of feeding it for free, at least for a while, was enough to tempt me out with the saw.

Inside the shed, the wood was strewn carelessly about, in all shapes and sizes. There was an old chest of drawers – warped by damp, and broken on top – and two squat cupboards, no longer usable. Several retired fence posts were stacked at the back, along with two or three thick logs which must have been cut from a fallen tree in the garden. Most of the wood though had built up during our work on the house over the past year: countless lengths of skirting board and v-lining, assorted scraps and offcuts, all thrown haphazardly into the shed, awaiting another use. Delving among it, I found many of the pieces familiar. As I picked them up and turned them over, I remembered the day on which they were discarded or the room from which they came. I recalled their various histories, and how they intertwined with my own. All of them now will end up in the same place, warming the house they helped to build. I gathered an armful of long sections – mostly skirting board from the dining room – and lay them outside on the ground; the smaller pieces I threw into a wheelbarrow by the doorway. When the barrow was full, I pushed it along to the work bench I’d set on the path and put it down on the far side, in easy reach. The afternoon was still. Out on the water, only a light ripple twisted the reflection of the houses across the loch and the half-clear sky. It seemed rude to be interrupting the day’s calm with the growl of an electric saw, but I didn’t have much choice. To attempt to cut all of this by hand would be a full time occupation. I would certainly warm myself with the effort, but I might never have the time to enjoy the heat of it burning. I had no option but to be noisy. Once plugged in and switched on, the blade cut easily, with a steady downward pressure. An incision, a wound, an amputation. It was rhythmic, almost hypnotic. The uniqueness of each piece of wood and its individual resistance to the blade became an irrelevance; every cut was exactly like the last. There was at first something disappointing about this. It was a strangely detached activity. My actions were machine-like and repetitive. Where sawing by hand demands energy and effort, all that this task required of me was time and electricity, and enough concentration to keep my fingers clear of the blade. There was no sweat on my brow and no ache in my muscles. The only slight discomfort was a niggling boredom at the rather mindless work. Yet the growing pile of wood was certainly satisfying. A few scattered chunks grew quickly into a mound of fire sized pieces. And when the first barrow load was finished, I filled another. And another. Wisps of sawdust rose like yellow smoke as the logs continued to clatter to the ground. I kept on like this for two hours, then three, without a pause. And while the work itself could hardly be called enjoyable, the result and the purpose were enough to keep me going. They were enough, even, to bring enjoyment. In another setting, such a job might be unbearably dull and robotic. But given reason for our efforts, the will becomes more robust and the work becomes easier. We need a point to our labour, it seems. In the end it was only hunger that brought me, almost reluctantly, back to the house, leaving behind two neat stacks of wood in the shed, all ready for the fire. Homecoming is the meeting between place and memory of place; it is the point at which past and present conjoin. And though the memory may be only weeks, days, or even hours old, there is always a distance to be crossed in the first moments of return. There is always a space between what is remembered and what is newly experienced.

When I stepped off the bus, just outside the front gate, it was lunchtime and the day was surprisingly mild. I was tired after travelling from Aberdeen on the boat overnight, and I was still a little shaky. It seemed the motion of the sea – which early in the morning had been throwing my belongings impetuously around the cabin – had been imprinted into my own muscles. It was a deep, shivering reflex that wore off only after several hours on dry, unmoving land. I walked slowly down towards the house, carrying my suitcase high so as not to drag it through the chicken shit that speckled the path. I’ve been away from home only three weeks. That’s not enough to leave me surprised by what has altered in my absence, but enough to be aware that it has altered. I looked around, trying to note the changes individually, but it was not easy to do. Defining the space between what is seen and what is remembered is hardest in those things most familiar to us. Like staring in the mirror after days without seeing your own face: what was seems to dissolve instantly into what is. The garden contained within it an accumulation of movement and growth which, together, amounted to a kind of swelling. The shadow of vulnerability that had clung to the place through the winter had lessened – released its grip a notch, or maybe two. Certain greens now seemed richer and less hesitant. Certain bushes now seemed less deceased. Right down low, the first bulbs have become flowers. Tiny snowdrops hang their heads forlornly here and there among the borders, like monks or mourners at a funeral. Alone in their display, the snowdrops are reluctant pioneers. They gaze always at the ground, as though ruing the genetic clock that brings them out of the soil so early in the year. On a day such a this, when a rumour of warmth softens the air, it is tempting to see these little flowers as brave heralds of the season to come, quietly sharing their song of spring with the garden. But the message is misleading. Unless this year is unlike all others I have known in Shetland, there is plenty of winter yet to come. The snowdrops are liars, but still they are easily forgiven. Their song is dishonest, but it is sung sweetly. Out on the side lawn, close to the trees, were two rabbits. It is unusual to see them here, so near to the house. When we first moved they were treating the garden as their own. At least one burrow, and possibly several more, lay in the back park. And every day we would watch them munching happily on the grass and among the beds. But their boldness could not last, for the cat very quickly made it known that such behaviour was unacceptable. From now on, while they were welcome to hang around, the consequences of doing so were not going to be ideal for the rabbits. One or two began to appear, headless, on our doorstep, and very soon the garden was a bunny free zone. As winter drags on though, they must be straying further. The pickings will be getting slim in the safest places, and so they become a little braver, a little more desperate. Either that or the cat has got lazy since I went away. Stepping into the porch, I turned and closed the door behind me, then put my bag down and went to sit in the living room. I was not thinking of anything in particular, just waiting, as though to catch up with myself. I felt deflated, exhausted, and inexplicably nervous. I lay back on the sofa and closed my eyes, readying myself to get home. I am on a train travelling west from Stockholm towards Karlstad. The carriage is clean and comfortable, and almost empty of passengers. Outside, the day is startlingly bright. Thin clouds hang loosely above us, failing to disguise the pale blue of the morning. The sun comes and goes, making me squint as I look out at the white world, watching it all pass hurriedly by.

Forests and farms appear and disappear as we gallop westward. Fields covered by snow stretch out all around, punctuated by red barns and farmhouses, each much alike to the other. The track is fringed by birch trees: leafless, white frosted and delicate. There are lakes too, distinguishable from the fields only by their uniform flatness. Most are marked by lines of footprints, sometimes human, sometimes not. And here and there a paddock of horses puff their hot breath into the frozen air. I close my eyes, rocked by the motion of the train, and begin to daydream. I am carried towards home. Even now, with eyes tight shut, I can see the snow, that great expanse of whiteness, flash printed on my retinas. But the farms and field are all gone. The lakes and horses are all gone. I see our front gate, in need of painting or replacing, and I walk through it, down the steps towards the house. No one has been here yet today, and the snow is unbroken. My feet leave their impressions on the path. But I don’t continue that way. I turn into the back park, where the snow seems deeper. It comes up almost to my ankles there, and I step carefully through it, trying to leave only clear unbroken prints. Out from the park, I walk down the lawn on the far side of the house, past the cottage and the greenhouse and towards the trees. I reach the bottom gate, and touch the loop of rope that holds it closed. It feels brittle and frozen, but I lift it and open the gate wide, then step down to where the ground is rough and lumpy underfoot. There between those trees is a long silence, one that seems to stretch out not just in space but in time, too. It is a silence that both encloses and includes me, and I submit to it without question, as though to make a sound would be to lose my place, somehow, and to be gone. The trees feel taller than they ought to be, and I cannot see from where I stand the edge that I know is only a few metres away. I cannot see the loch at the end of the garden, nor the park where the sheep should be grazing. The trees are thicker than they were before, and I wonder how they can have grown so much in the short time I have been gone. Perhaps these little trees have rebelled and risen up, like a mutinous army, to join the boreal forest of Scandinavia, Siberia and North America. No longer a tiny island of pine and spruce, willow and larch, they have reached out and caught hold of their neighbours across the water. They have become an unbroken line. Or perhaps I am wrong. Perhaps I am no longer at home at all, but lost somewhere in that great forest that wraps itself like a shawl around the north. I may never find my way back from here. But no, when I turn around I can still see the open gate, and beyond it the house. And so I begin to walk in that direction, my feet now slow and heavy beneath me. Halfway across the lawn, I stop. Things are less clear now, and I am no longer sure of where it is I am supposed to be going. I stand still for a moment, feeling lost and unable to think, and as I do so I begin to shake, gently, rhythmically, and I remember that I was not at home a moment ago. That I am not at home now. Instead, I am rushing westward through Sweden on a clean, quiet train. The garden disappears, melting from around me in an instant. And all that remains is the snow. I have begun to think of the year ahead, and I have begun to act on those thoughts. Yesterday, walking back to the house from the hen’s shed in the morning, I tried to imagine how things might look in six months time, and what I could do to help that happen. I thought about jobs that needed attending to, and others that soon would. I began, quietly, making plans.

Perhaps it was the sight of those green fingertips emerging from the soil, all around the garden – the little bulbs returning to life after their long slumber. These are the first signs of change, and they are as welcome as the sun after a storm. In every bed they are emerging. Beneath bushes and trees they are coming: tiny spears of life; tiny shoots of anticipation. I got up late this morning, but with no other plans for the day, except to be outside. I dressed, ate breakfast and drank my coffee, then put on my outdoor clothes and opened the door. The garden has been neglected over the winter, and it shows. On the lawn, leaves have fallen and rotted in ugly piles. The job of clearing them up, which I avoided when they fell, has now become a more difficult task for yet another day. In quiet corners sweet wrappers and plastic bags have blown and settled, and found new homes. Last year’s blooms have lain where they fell; the beds still are cluttered and untamed. The trouble is, I’m not a gardener. Buying this house we have inherited a piece of ground that was created over six decades. And though different owners have shaped it in different ways, it has taken consistent care and effort to keep it as it has been. But it has also taken knowledge – an understanding of what was required to make things as they were supposed to be. I don’t have that knowledge, or that understanding. Out here I am ignorant. And blind, too: blind to the possibilities of this piece of ground. For gardening is not just a response to what is already there. It is also a response to what is not yet there – to the imagined garden. A space like this requires steering. It requires the vision and will to push it in the right direction. There are many things I would like to change here. And in my head I can see – vaguely, distantly – the garden that I wish one day to have. But as yet I don’t know how to get there. Up by the workshop – a one-room building referred to by us and our predecessors here as ‘the cottage’ – two tall bushes had been threatening the gutter and the roof, with the help of a persistent ivy plant, whose sticky fingers had already reached in beneath the profile sheeting. I had decided, on this mild, still day, to do something about it. It was a simple and satisfying job, with long-handled shears, to cut the bushes back to a manageable size and to strip the ivy back to the ground. I enjoyed feeling them take shape as I worked, and the hours passed quickly. When I had finished, twigs and branches lay all about me in a tall, chaotic pile, and one corner of the garden had changed entirely. It was neat, and under control. It was as I wanted it to be. As the sun began to soften in the afternoon, I finished tidying the branches away and stood by the gate to the back park looking around. I tried then to see the garden not as it was, or as it would be this summer, but as it could be in five or ten years time. I looked behind me, to the park still matted and overgrown by grass, and I tried to untangle it and to create something good. I made sweet, black earth rise from beneath the grass, and I made vegetables rise from beneath the earth. I reminded myself that all this once had been a hay park – before the house, before the garden – then I returned to the work of imagining. I have recently hung a bird feeder from the willow at the back of the house. It is a modern looking contraption – rocket shaped, with a clear plastic saucer at the bottom to catch some of what is spilled.

It has been fastened halfway up the tree to make it easy to see from the window. After all, feeding the birds is only ever partly for the birds’ benefit. Much of the pleasure belongs to those who provide the food. Though strong winds have several times made it unusable over the past few weeks, it has been a popular addition to the garden. Yesterday, once again, the feeder was hanging empty from the branch. And so, once again, I went out and removed it, unscrewed the top, poured in the dry mixture of seeds and mealworms, returned the feeder to the tree and then returned to the house. Nothing stirred at first except the hens, who shuffled confidently beneath the tree, kicking about in search of anything I might have dropped. They found little, but knew not to stray too far. The first to the feeder was the robin, nervously looking about before taking a mealworm in its beak. The bird twitched furtively, as it always does, and stayed only a moment before retreating to the safety of a bush. Then, at once, came the starlings and the sparrows – a horde of twittering, bickering birds. The sparrows held back on the outer branches but the starlings had no such patience. They barged each other out of the way, fighting to be closest to the action. Beneath a torrent of wings, the feeder swung precariously. Down below, the hens’ patience was being repaid, and the pair made short work of anything that fell. Two collared doves, then three, landed on the lawn and joined them in the flower bed. And a blackbird, last of all, came to take its place in the shower of seed. But something spooked them. All activity ceased and the birds were still, as though listening for something. One starling flew, and then all were gone. The sparrows, doves and blackbird too. And the feeder was left unattended. Five minutes later, the procession was repeated. The brave, nervous robin came first, alone, and left. And then, a flurry of wings and feathers. This afternoon, sitting writing at the dining room table, I could hear the birds were still about, though not in such numbers. When I lifted my head, I could see only a single starling in the tree. This one bird remained for much of the day. Every time I looked up, it was there, scraping the last of the food from the plastic tray. I could hear it too, talking loudly to itself in the absence of companions. And then the noise grew more insistent. In a second, it rose to a fearful squall, three times, four times, then nothing. I stood up and went to the window. On the ground was the sparrowhawk, pacing about in the flower bed beneath the tree, three metres at most from where I stood. Arriving after the event, it wasn’t exactly clear what had happened. I could no longer see the starling, though there was no doubt it had been hit. The sound alone was confirmation enough, but from this close I could see blood on the talons, and a little puff of downy feathers lying on the soil. Perhaps it had escaped the hawk’s clutches and managed to hide in the undergrowth. That, anyway, was what the hawk seemed to think. It was wary – too close to the house for its comfort – and it stopped repeatedly in its search for the starling, looking and listening, then rummaging about again in the dead leaves and stalks of the bed. For a moment it disappeared, pushing its way behind the bushes, against the fence, and then it was back, the look of bafflement and frustration almost palpable in that perfect, expressionless face. The hunt couldn’t go on. It was reluctant to give up the prey, but the starling had disappeared. And so, suddenly, did the sparrowhawk. It lifted and was gone. All that was left was that little clutch of feathers, and the feeder, once again hanging empty. At eight o'clock, the garden was ripe with shadows, each one sharpening against the dull edge of the morning. Gradually, a grim pink was unveiled through cloud cracks in the east, then lost again. And by the time the sun rose, just after ten past nine, grey daylight hung low over the valley, as though weighed down by the effort of its own becoming. There was no bright sunrise, no glorious, golden dawn, only a slow and reluctant undarkening.

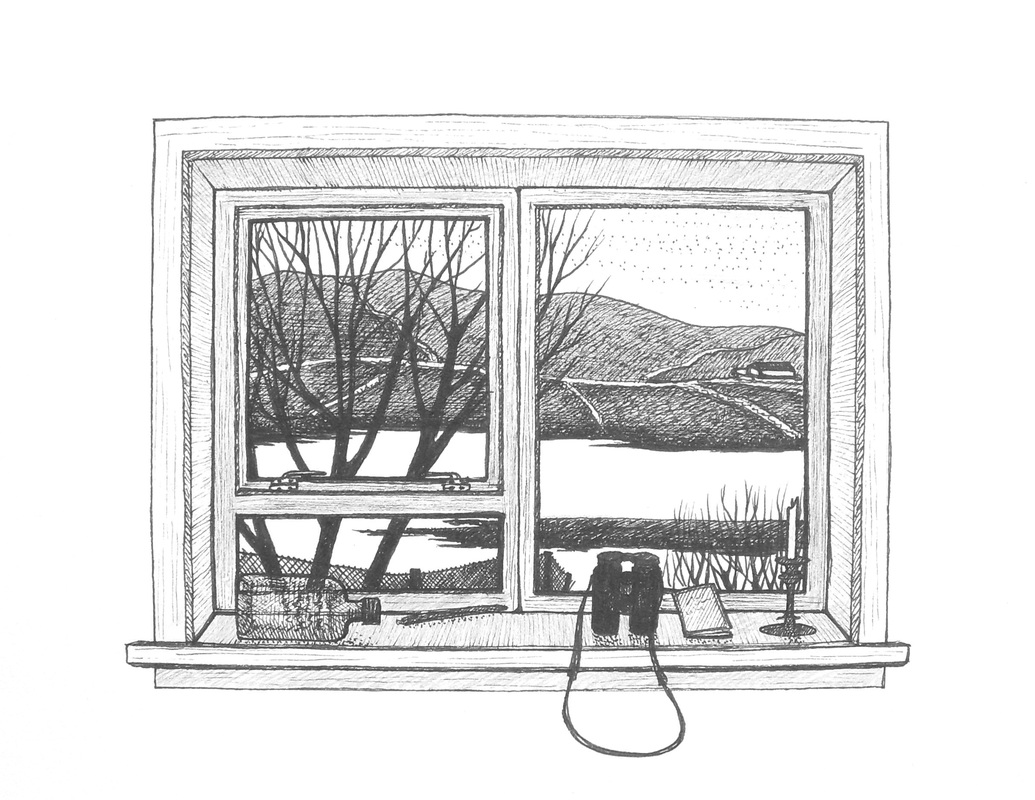

This was the shortest day: midwinter. Most often it falls earlier, on the 21st, but it seemed that even the solstice was sluggish this year. Today, the sun held above the horizon for just over five and a half hours. Tomorrow, the nights will begin to shorten and the days to lengthen out. Spring, I suppose, is on the horizon. I did not rise easily. During the night I was woken by the wind, then held awake by the rushing of my own thoughts. It took me a long time to sleep again. When I opened my eyes just before eight, both had quietened, though not entirely calmed. The first sound I heard was the chattering of crows from just outside. These grey mornings make it hard to be cheerful. Particularly when they give way to grey afternoons and black, starless nights. They make it hard not to long for winter to pass, and for warmth to creep in again, spreading generous green light around the garden. I longed for that today as I watched dawn roll so hurriedly into darkness. Of course, there are few things more stupid than longing life away. Each day that falls behind is one fewer left ahead, and even as I gaze impatiently into the garden, I regret my willingness to wish a winter gone. I regret how one moment after another can pass with such terrifying haste and yet still seem to be moving too slow. But it seems I cannot help it, and that troubles me. It keeps me awake at night. Bound up tightly with all this wasteful impatience is a kind of physical restlessness that is as familiar as it is unwelcome. At this time of year, it pulls at my sleeve like an impatient child, urging me to go and to keep going. There are, in Shetland, those who acknowledge that pull and follow it. A few spend their summers here in the islands and then fly south – usually to New Zealand – to enjoy another summer. Like migrating birds, these people stay always a step ahead of winter. Perfectly natural, some might say. Perfectly normal. We are, after all, a restless species: nomads, wanderers, pilgrims. One thinks here of Bruce Chatwin, and his claim that 'Evolution intended us to be travellers'. Human beings are hard wired to keep moving, he insisted, and their relatively recent propensity to stop and settle down has led to all manner of social and psychological problems. 'I like to think that our brains have an information system giving us our orders for the road' he wrote, 'and that here lies the mainsprings of our restlessness'. The only antidote, according to Chatwin at least, is to heed its call and go. But mostly I do not go. Mostly I resist. And in part I resist because I disagree. Restlessness is not a craving that can be satisfied simply by giving in. It is not a thing that can be physically escaped or left behind. Like an itch, the scratching of it does not always soothe; it may exacerbate. But I resist, too, for another reason. Wherever I have travelled in the world, and for whatever reason I have gone, my restlessness has morphed almost invariably into homesickness. My thoughts, which here will wander towards paradises not yet found, soon make their way back to that paradise I have left behind. And the longer I stay away, the more insistent these thoughts become. In the late 17th century, when homesickness was first described by the physician Jonnaes Hofer, it was given the medical name, nostalgia, derived from Greek and meaning, roughly, the suffering caused by a longing to return. Hallucinations, nausea, loss of appetite and indifference to the world were among the many symptoms. Those who suffered most were invariably soldiers, most often from Switzerland or from Scotland. City dwellers rarely succumbed; those from farms and rural areas were worst affected. Over the years, there were numerous suggested remedies for this strange and debilitating illness: leeches, opium, purging of the stomach, busying oneself with 'manly' activities and, during the American Civil War, public ridicule. But ultimately most doctors agreed that there was only one guaranteed cure, and that was to go home. And so here I am, afflicted by restlessness when at home and by homesickness when away. One might be forgiven for pronouncing mine a hopeless case. And one might well be right. But while these two urges have seemed to rage and argue within me always, I am no longer convinced that they are in fact so very different. Rather, I wonder if they might not be, at root, two strains of the same malady: one, a longing for an imagined future; the other, for an imagined past. Both restlessness and homesickness are symptomatic of a disengagement from the present moment and the present place – an exile that manifests itself as an impulse to flee, either in one direction or the other. Evaluating our own emotions, we routinely misdiagnose the causes of that impulse, but it seems to me that somewhere at the heart of it all must be the desire to end our exile – to become fully present – and to be, in every sense, at home. So why then are my feet and fingers twitching? Why do I hear this siren song, persuading me to go? In what way am I disconnected from the now and the here in which I find myself, on this black evening, in this chair beside the window? The answer may be simple. It may be only that I am on the wrong side of the glass. In these short, dark days, I am not often outside. My experience of the things around me is mostly indirect and non-participatory. I see the garden for a few hours and then it is gone. And if I did not work from home, I would barely see it at all. For most people in Shetland, at this time of year, it is dark when they leave home in the morning and dark when they get back at night. For five or six days in a week, the world outside is known only by memory. I suspect that were I to be out there every day, either working in the garden or even just crawling about in the dirt, I would be a more satisfied person. I would be cold and damp much of the time, but this in itself would not equal unhappiness. Indeed it would surely engender a deeper sense of gratitude for those comforts that I find inside the house. I would be healthier, being well exercised, and I would certainly sleep better at night. I have a feeling too that my restlessness would weaken, and that perhaps I would be more fully here. Such a life has its appeal, undoubtedly, but without a farm or a croft it is hardly a practical option. While I might enjoy hauling on my wellies every morning and splashing around in the mud, a full time devotion to such activities might require certain personal and financial sacrifices. And because of that – because it is optional – a bit of bad weather is enough to keep me inside for days at a time. There is surely a discipline, then, to engaging more fully with place. I am thinking not just of a determination to go outside, whatever the weather, but of a kind of attentiveness – a conscious effort to notice and to be aware – that might bring one's surroundings more clearly into focus. In suggesting this, I am skirting deliberately around the word mindfulness, and pushing towards something less centred on the self. That something could best be called placefulness: a way of imagining and understanding one's relationship with place and one's participation within it; a way of acknowledging those connections that bind us to the present place and time; a way of living with both past and future, without longing for either. The problem with the shortest day is that it is gone too quickly. In these mid-winter weeks, light arrives then disappears, and the opportunities to enjoy it pass swiftly by. And when the night does come and darkness surrounds the house, I find myself standing sometimes beside the window, looking out to where the garden ought to be. With the lights switched on and the world wrapped in black, the cold glass becomes a mirror. All I can see there is myself. |

The Things Around MeThe Things Around Me is the story of a Shetland garden, written by Malachy Tallack and illustrated by Will Miles.

Archives

October 2016

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed