|

On dry days I have been outside as much as time allows, finding jobs to do in the greenhouse or among the borders, or just walking through the garden and watching as things progress. Beneath the trees, scores of green shoots are growing taller. Daffodils and bluebells are among them, though only the snowdrops and purple crocuses, which crouch timidly under bare bushes, have opened so far.

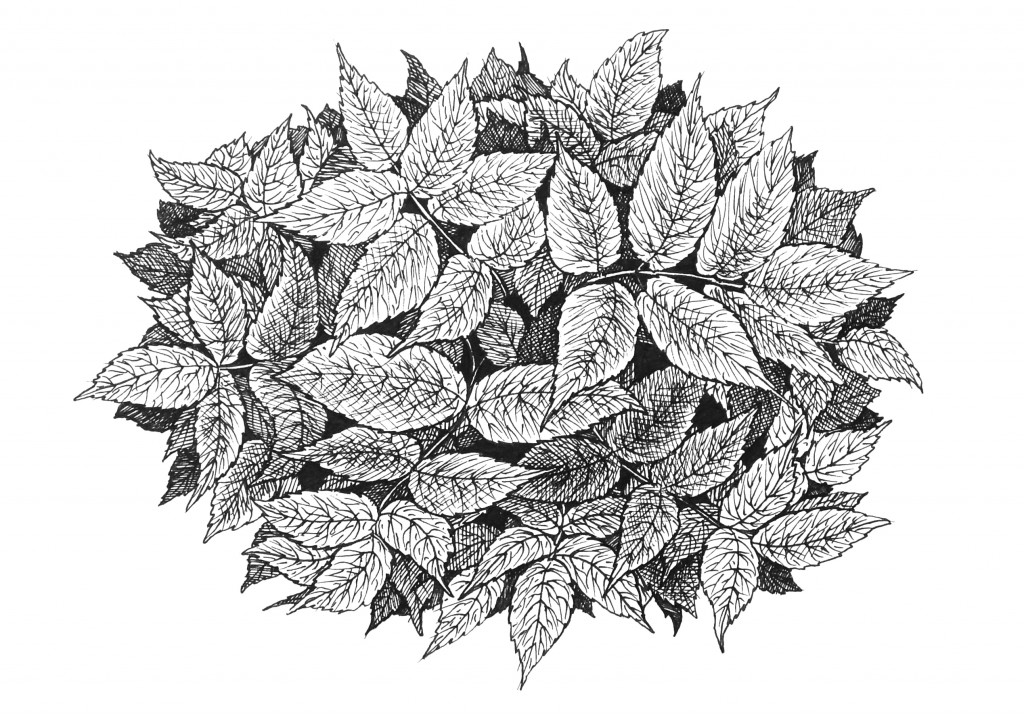

There is a kind of relief to be found on these wanders. At times when I feel burdened by the thought of tasks as-yet-undone, it makes me glad to see what flourishes without any intervention. These bulbs would grow whether I was here or not; they are reliable, predictable, determined. My pleasure at these sights though has been tempered by the appearance of another early riser: an unwelcome guest in the garden. On the edges of the upper and lower patches of trees, in the back park and throughout the semicircular flower bed in front of the house, clusters of bright green leaves are emerging and unfurling, pushing their way up towards the light. Being an entirely inexperienced gardener, I had no clue about the identity of this plant when we first moved here, less than a year ago. And even when I was informed of its name – ground elder – it meant nothing. Now, however, the sight of these new leaves makes me shudder. Before long they will have grown into a rampant, sprawling mass, like an infection in the earth. Ground elder is among the most feared of weeds, and for good reason. It is extremely invasive, and can quickly dominate a garden, swamping and crowding out other plants. It is also extraordinarily difficult to remove once established. And established it certainly is. Part of the problem with ground elder is that it spreads below the soil as well as above it. Long threads of root, called rhizomes, extend outward from each plant, sometimes in several directions. And as these rhizomes burrow away from the parent, they send up new shoots, gathering more energy and taking up more space. The result is a tangle of leaves above ground, and a tangle of roots below it. It is difficult not to ascribe evil intentions to such a species. There is something monstrous and nightmarish about this plant, after all. I imagine it like an enormous web, spread out beneath the surface of the garden, and at its centre, somewhere, must be a dark heart. Find that, and the beast may be slain. Sadly, the truth is worse: there is no heart to find. To kill ground elder it must be removed completely, piece by piece, or else starved of light for long enough to stop it growing. The former method is more practical for most people, but more risky. For like a severed tentacle that can regenerate an octopus, the tiniest piece of root left in the ground will grow again. Digging it out must be done with care – slowly and meticulously. The only other alternative is chemical weedkiller, to which, in agonising defeat, many a committed organic gardener must have been driven. It is standard practice these days to extend a certain sympathy towards weeds. These plants that cause so much trouble and frustration can become metaphorically entangled with the idea of ‘wildness’. In this conception, weeds are the forces of the wild, fighting against the civilising army of people, clawing back the land that we try to domesticate. It is them against us. For the most part, this is nonsense. And in the case of ground elder, it is complete nonsense. Weeds are exploiters of the human; they thrive because we thrive. More urban fox than timber wolf, their preferred natural habitat is not a wilderness, it is a cultivated garden with a lazy gardener. The history of ground elder is inseparable from the history of people. For this is not a native Shetland species, reclaiming its territory. Nor is it even a native British species. Ground elder was taken north from continental Europe as a food source by the Romans, who found the British Isles rather lacking in edible greenery. Later, in the Middle Ages, it was moved around by monks, who considered it a cure for the gout with which they were plagued. Today, it is mainly gardeners who carry it from place to place (as well as the wind, of course). A tiny sliver of rhizome hidden among the roots of an ornamental plant, transferred from one garden to another, is all it takes to cause a whole lot of trouble. That, most likely, is how our own colony arrived. Walking the edge of the curved flower bed out front, which is riddled with the stuff, I leant down and plucked a few of the plants. In Scandinavia, it is still often eaten, either raw in salad or cooked as an alternative to spinach, and I put these tiny leaves in my mouth and chewed. They were tangy – an odd, distinctive flavour that I certainly wouldn’t call pleasant. Not good enough to forgive the weed; and certainly not good enough to allow it to remain. Comments are closed.

|

The Things Around MeThe Things Around Me is the story of a Shetland garden, written by Malachy Tallack and illustrated by Will Miles.

Archives

October 2016

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed