|

If there is one thing upon which it is almost possible to depend in Shetland’s unpredictable and eclectic climate, it is the wind. As an exposed and relatively low-lying archipelago in the North Atlantic, we get our fair share and more of strong winds, gales and storms. The upper echelons of the Beaufort Scale are familiar – sometimes wearyingly familiar – territory.

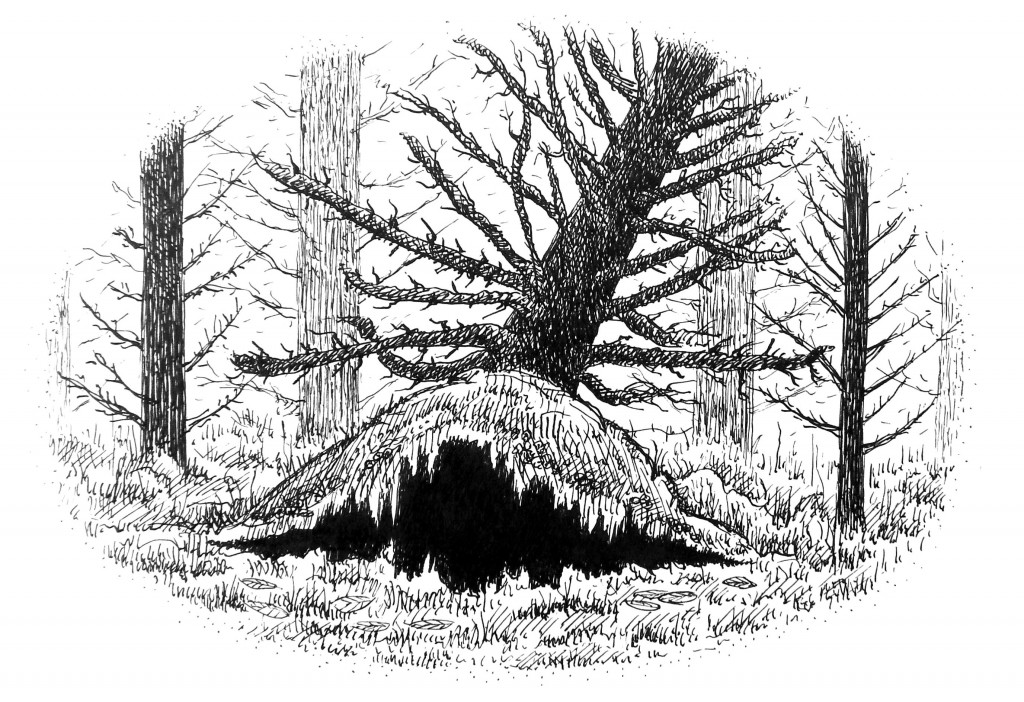

Over the past couple of weeks, we have been treated to several, sometimes prolonged, incursions into that territory. Gale has followed gale, with little respite between. Twelve days ago a gust of 90 miles per hour was recorded; and last night was even worse, with gusts reaching up to almost 100 miles per hour. This is not exceptionally strong for a Shetland winter, but it has been particularly unremitting. As in all places where extremes of weather are to be expected, life adjusts. Buildings are constructed with winter in mind, and when forecasts are bad, anything that might move is either tidied up or tied down: plant pots, wheelbarrows, sheds, caravans. It is remarkable what a bit of wind can do. Inside, we separate ourselves from it, sheltering in our bubbles of stillness – behind curtains, beside fires. Like passengers in a speeding car, we are disconnected from the violent pace of what surrounds us. But when the wind really blows, as it did last night, it becomes impossible to hide from it. The air whistles under doors; it batters and rattles windows; it howls and growls and hisses and screams. A strange, inexplicable fear can rise out of this din: the fear, perhaps, of being consumed by something wild and monstrous. “I always feel the wind as a bad-tempered thing” wrote John Stewart Collis, “and my mind contracts in resisting it, and I can enjoy no pleasant, expansive thoughts when ruffled by its peaceless, ceaseless wave”. This morning did not exactly bring calm – a force eight gale blew for much of the day, with gusts of 60 miles an hour or so – but the worst of the storm had passed. There was that shimmering sense of relief that comes when a threat is lifted – when the grizzly bear steps away from the cabin door and the sound of its bellow abates. At once, other details emerge. You become aware, firstly, of yourself: the stiff heartbeat and the first conscious breath. Then the world, as it was, returns. I took a walk around the garden this afternoon, looking for damage and for an excuse to be outside. On a whim, I hopped up on to the wall below the ‘upper’ trees, and pushed my way in among them. At once I felt more sheltered and more vulnerable than I had outside. Here the wind was changed – not subdued, exactly, but constrained, as though held on a fraying leash. The sound was amplified, too, roaring up among the evergreens, which swayed precariously and unpredictably beneath the weight of the air. Here and there were broken branches, hanging loose or lying where they’d fallen among the rotting leaves. One tree had tipped a little, exposing a wedge of severed roots and soil. Then, further up, a pine was leaning over at 45 degrees, resting hard against the trunk of another. At its base was a semicircle of earth about three metres across, with a dark hollow lying beneath. There was something poignant about this sight, and I walked slowly around it, reminded again of somewhere far away and long ago. I was six years old, almost seven, when the ‘Great Storm’ of October 1987 hit, blowing over an estimated 15 million trees in Britain. I can just recall walks near our home in the south of England in the months that followed, among forests changed forever by the strength of that wind. And it is those hollows that come back to me most clearly – deep holes in the ground where roots once had been, with headstones of earth now towering above. A biting shower of snow bristled around me as I stood there beside the tree, watching it, still rocking gently from the force of the wind, like the quieting beat of a heart. 13th December That last storm was followed by three days of cold and relative calm, the loch shifting between light ripples and mirror stillness, edged by a fragile skin of ice. The valley becomes smaller at such times. Sound is unhindered. The bark of a dog from across the water is loud and disconcerting. The yell of a crow seems to come from everywhere at once. Stillness like this does not feel like a zero point or a state of equilibrium, but, rather, like an absence of wind. Calm, in its way, is just as shocking as a gale. If there is balance, it lies somewhere in between. Comments are closed.

|

The Things Around MeThe Things Around Me is the story of a Shetland garden, written by Malachy Tallack and illustrated by Will Miles.

Archives

October 2016

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed