|

Each evening, when the hens have retired to their house, one of us must go and close the door behind them. The birds are entirely free range, roaming around the garden, kicking up mud and leaves in the flower beds, picking their way methodically through the lawns. They make a mess, but for now it is tolerable, and they do pay their way in kind.

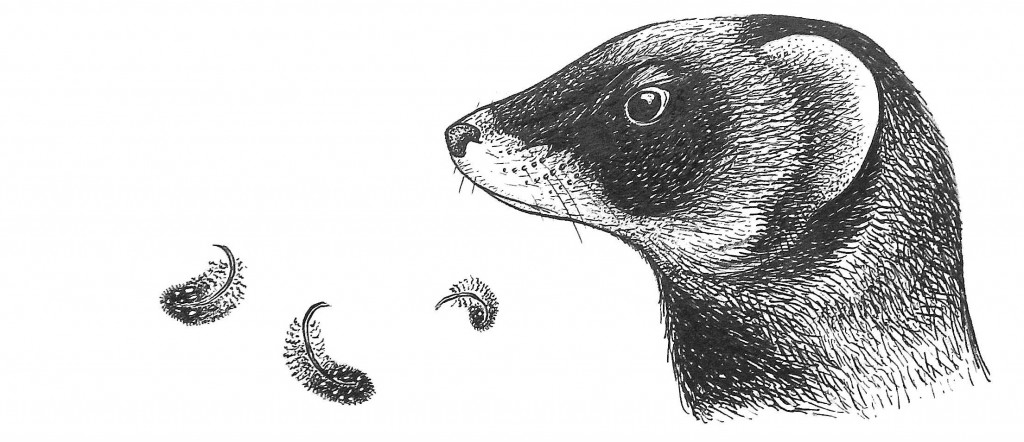

When it reaches a certain time of day – or more specifically a certain level of light – the hens cease their wandering and head home to one of our sheds, which is accessed by a hole in the wall, with a ramp both inside and out. Once they’re in, it is up to us to close the door. Tonight, on my way out to a meeting in Lerwick, I did just that – lowered the little wooden door and fixed it in place. Then I looked inside the shed to make sure there was food and water, and to see that everything was okay. Everything was not okay. We have – or had – three hens, all Rhode Island Reds, with subtle differences in colour, character and social status. The lowest ranking of these was also the tamest, with one characteristic perhaps compensating slightly for the other. She was, in addition, a layer of enormous eggs. Recently though, this particular bird had adopted a bad habit of roosting on the ramp just inside the entranceway rather than jumping up to the perch alongside the others, and it was almost certainly this habit that cost her her life, for when I arrived in the henhouse she was lying beside the door, virtually intact but unquestionably dead. At the back of the coop, now deprived of an escape route, was the foul-smelling culprit. There are no native land mammals in Shetland but several have been introduced over the centuries and have made the islands their home: house and field mice (which have been here long enough to evolve into sub-species), otters, rats, hedgehogs, rabbits, mountain hares, stoats and, undoubtedly the least popular of all, polecat-ferrets. This hybrid, with its familiar robber-mask markings, only appeared here about 30 years ago. Whether first released deliberately or accidentally is unclear, but they bred and now thrive, eating rabbits, wild birds, eggs and just about anything else they can find. Given the chance they will also eat hens, and once inside a henhouse they will often as not kill everything. This particular individual was interrupted in its task by my arrival, which was lucky for me and for the two remaining hens, but considerably less so for the polecat-ferret. Standing on its back legs in the corner of the shed, it was looking for a way out. My choices were limited. If I opened the door and let it go, there was little doubt it would be back the following night to finish the job. As I had no interest in losing any more hens, I could not let it go. Not for the first time, I regretted not owning a gun. The chicken wire that separated me from the polecat was reassuring. While it was alive and still capable of biting me I would have preferred to stay separated; but that wasn’t going to be possible. The only solution I could see was the shovel leaning up against the wall, and that was a long way from ideal. I picked it up reluctantly and the decision was made. The temporary stalemate within the henhouse was immediately broken when I undid the latch and stepped through the gate. One of the birds, which had so far been as still and quiet as if they had been sleeping, saw in that instant an opportunity to escape. In a flash of feathers she leapt over my shoulder and out of the shed door, squawking all the way. Her companion, now more terrified than ever, just sat still, her eyes fixed on me, then on the floor, then on the shovel. In the time it took for the first hen to flee, the polecat-ferret had moved from the back wall towards the hatch, and finding it closed had curled up in the narrow entranceway, putting itself almost out of reach. It is at moments like these that we see things that may not be there: complex thoughts and emotions in an animal whose face we cannot truly read. At moments like these we see a kind of distorted mirror, where the muddle inside of us is reflected in the eyes of another creature. I did not see fear in the polecat, nor aggression. Though it must have experienced some kind of anxiety, the hopelessness of its situation – trapped in a cage with nowhere to go – seemed to bring out something more complicated and unnerving. A strange kind of resignation was what I saw: an absence of panic. The polecat seemed calm, as though it understood, in a way that it could not possibly have done, that the game was definitely up. When I swung the shovel against the wall to try and dislodge the animal from the entranceway, the polecat didn’t bolt as I’d expected. It unfurled itself out into the coop, then walked slowly back to the far corner, where it stopped still and waited. I lifted the shovel again. When it was done, I removed both bodies – bird and animal – and laid them in a cardboard box to deal with in the morning. I stayed with the one remaining hen for a few moments, waiting for her to calm down again and for quiet to return, then I switched off the light and flicked my torch back on. I had long since missed my meeting in town. I wondered then how I would feel if this creature were native. Had it not been a recently-introduced pest – a threat to both wild and domestic birds – could I defend my actions so easily? After all, were it to speak, the animal might quite justifiably say to me: “I was here first”. The polecat doesn’t need to talk, of course. I know the questions, and I know that my answers do not entirely release me from hypocrisy. But I do not feel guilty. As I came back down the path towards the house, I saw that our cat had found a juvenile blackbird and was waiting for a chance to finish it off. The bird was flapping against the windows and walls, unable to lift itself high enough to be free. I picked it up and chased the cat away, then held my arm in the air. The blackbird opened its wings and vanished into the night. |

The Things Around MeThe Things Around Me is the story of a Shetland garden, written by Malachy Tallack and illustrated by Will Miles.

Archives

October 2016

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed